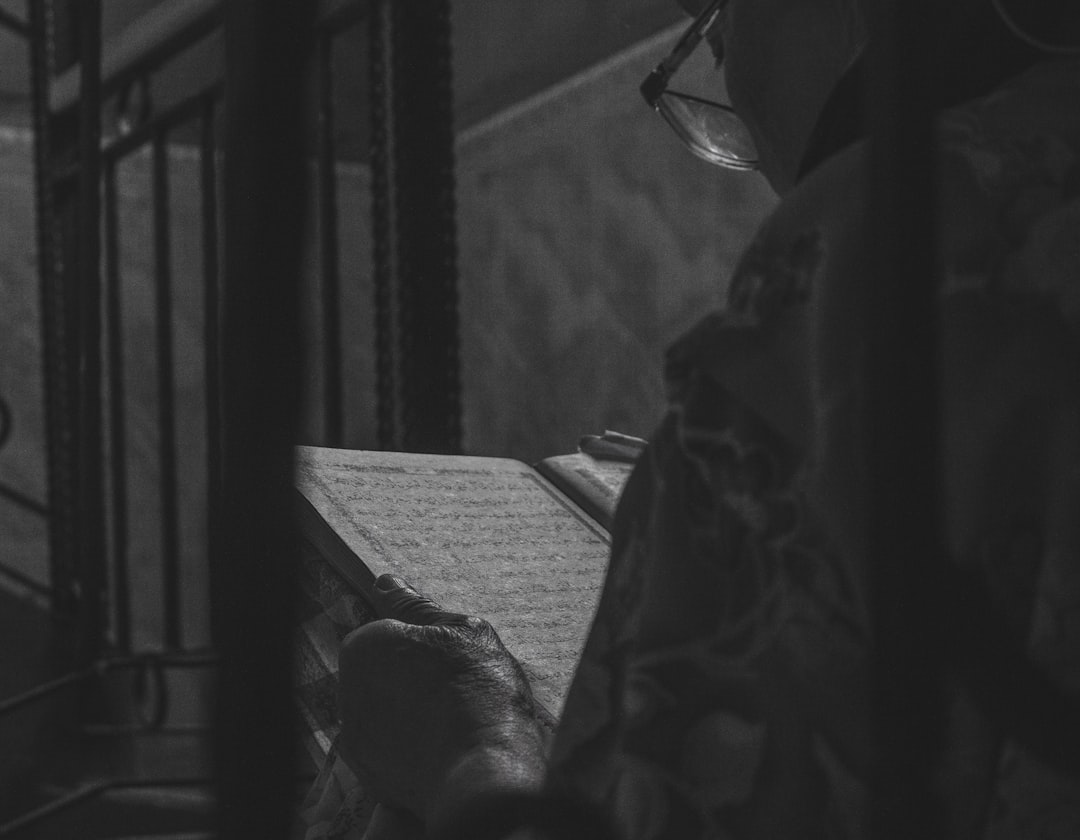

When the pen meets the page, it carries not just ink but centuries of cultural exchange. In the medieval Islamic world, Arabic and Persian poets entered a dynamic dialogue—borrowing rhythms, forms, and imagery—that forged two of the planet’s richest literary traditions. This “fruitful encounter” reshaped the very idea of what poetry could be, creating a shared toolbox of meter, genre, and rhetorical flair.

1. Historical Backdrop: Conquest and Conversation

-

7th–8th Centuries: The Arab conquests brought Persian lands into the orbit of a new lingua franca, Arabic. While Arabic became the language of scripture, law, and high culture, Persian—spoken by administration and the masses—remained vibrant.

-

9th–10th Centuries: As Persian dynasties like the Samanids revived local rule, court poets began writing in “New Persian” using the Arabic script—and consciously drawing on Arabic poetic models. What followed was less cultural replacement than creative fusion.

2. Prosody Passed Eastward: From ʻArūḍ to New Persian

-

Arabic ʻArūḍ: Codified by al-Khalīl ibn Aḥmad (d. 791 CE), Arabic prosody rests on patterns of long and short syllables—creating meters like Ṭawīl, Kāmil, and Rajaz.

-

Persian Adoption: Pioneering poets such as Rudaki (d. ca. 955) and Farrūkhī Sīrjānī adapted these meters wholesale to Persian. Suddenly, a system born in Arabic desert odes governed the rhythm of Persian couplets—laying the foundation for the great epics and ghazals to come.

3. The Qasīda’s Long Shadow

-

Arab Qasīda: A grand, monorhymed ode—often opening with a nostalgic “nasīb” (desert-camp love-scene), proceeding through praise, and concluding with moral or political reflection.

-

Persian Qasīda: Court poets made it their own:

-

Panegyric Focus: Celebrating Samanid and later Ghaznavid patrons, poets showcased loyalty, valor, and munificence.

-

Local Color: Descriptions of Persian gardens, caravanserais, and wine-halls replaced Bedouin sands and camel caravans—yet followed the same formal blueprint.

-

4. Borrowed Brushstrokes: Rhetorical Devices

-

Badīʿ (Embellishment): Poetic devices—metaphor (istiʿārah), simile (tashbīh), pun (jinās), and more—originating in Arabic balāghah manuals became core to Persian stylistics.

-

Shared Glossaries: Persian rhetoricians like Jamāl al-Dīn al-Isfahānī wrote Persian treatises on these devices, translating and expanding Arabic sources—creating a pan-Islamic toolkit for verbal ornamentation.

5. Themes and Imagery: A Two-Way Street

-

Arabic to Persian:

-

Wine and Tavern: While wine features in both, Persian poets layered on local vineyards, rose gardens, and saffron-scented breezes—transforming Arabic “khamr” into a symbol of spiritual as well as sensual delight.

-

Desert vs. Garden: The harsh Bedouin landscapes of Arabic odes gave way to the lush chahar-bāgh gardens of Persian imagery—yet the underlying motifs of exile and return remained universal.

-

-

Persian Echoing Back: As Persian verse rose in prestige, Arabic poets in Baghdad and Córdoba began borrowing its images—cypress trees, nightingales, and Beloved’s cheek as “pomegranate-blush”—integrating them into their own ghazals.

6. Bilingual Poets: Living Bridges

-

Abū Nuwās (d. ca. 815): The consummate libertine poet wrote famously in Arabic but knew Persian lore—and may have inspired later Persian wine-poetry tropes.

-

Unsūrī (d. ca. 1039): Prolific panegyrist under the Ghaznavids, he composed qasīdas in both Arabic and Persian, experimenting with how each language’s rhythm and register could amplify praise.

Their careers illustrate that the “frontier” between the two literatures was not a wall but a marketplace.

7. Synthesis and Innovation: Forging a New Tradition

By the 12th century, Persian poets were doing more than imitation:

-

Ghazal’s Rise: Although the Arabic ghazal existed, Persian poets expanded it—making it the dominant lyric form, rich in allusion, wordplay, and mystical undertones.

-

Mathnawī Narratives: The rhyming-couplet epic, exemplified by Rūmī’s Mathnawī, fused Persian narrative instincts with Arabic metaphysical inquiry—crafting long, allegorical journeys into the heart.

The result was a literature that honored its Arabic inheritance while staking out a distinct Persian voice—melodic yet powerful, ornate yet deeply human.

8. Enduring Legacy

-

Across Empires: From Ottoman Istanbul to Mughal Delhi, the intertwined Arabic-Persian poetic heritage underpinned courtly culture for centuries.

-

Modern Poets: Today’s Persian-speaking and Arabic-speaking writers still draw on these shared meters and motifs—testifying to a dialogue that began over a millennium ago.

“In the vineyard of words, two vines intertwine—each drawing strength from the other’s root.”

The early encounter between Arabic and Persian poetics reminds us that great art flourishes not in isolation but at the crossroads of cultures—where poets listen, learn, and transform what they inherit into something utterly new.