Introduction

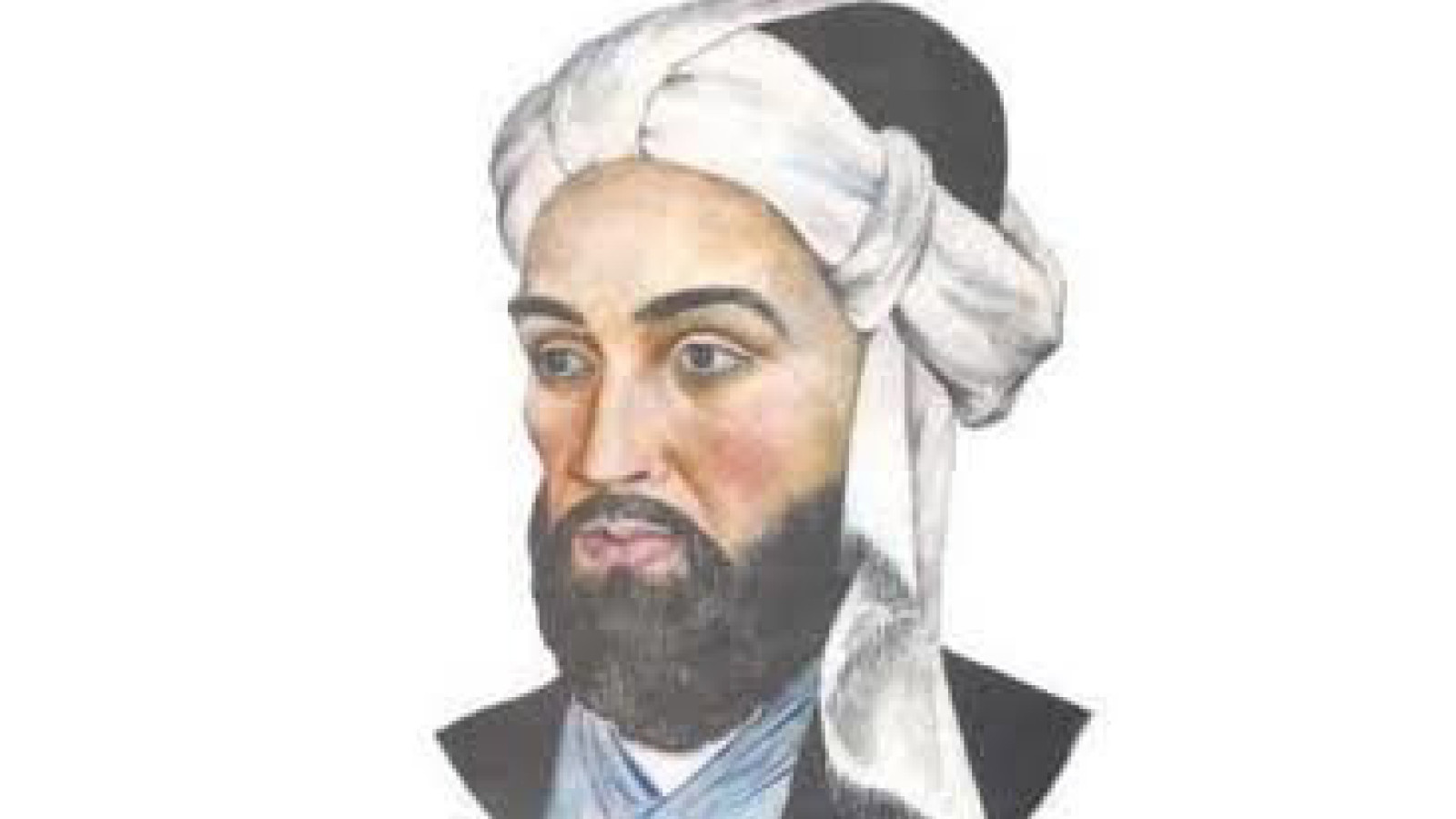

In the grand tradition of Persian courtly verse, few names loom as large—or cast as long a shadow—as Anvari (Awhad ad-Dīn ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad Anvarī, c. 1126–1189 CE). Celebrated for his dazzling command of language and intricate rhetorical flourishes, yet feared for the scathing sharpness of his satire, Anvari was the undisputed master of the qasīda—the grand panegyric ode. Through his life and work, we glimpse both the glittering heights of medieval Persian literary culture and the perilous politics of Seljuk patronage.

The Poet and His Times

Born in the northeast Iranian region of Abivard, Anvari came of age under the Seljuk sultans who ruled a vast empire stretching from Central Asia to the Levant. Poetry was not mere pastime but an essential vehicle of political legitimacy: a well-crafted qasīda could immortalize a ruler’s victories, magnify his virtues, and secure lavish rewards—farmland grants, robes of honor, and princely titles.

Anvari’s meteoric rise began in the court of Sultan Ṭughtījīn (r. 1161–1176 CE), where his erudition and astonishing facility with language earned him the honorific “Amīr al-Shu‘arāʾ” (“Prince of Poets”). Yet his tongue wielded equal power in praise and persecution: ministers who fell short of his exacting standards soon found themselves the target of withering lampoons.

Mastery of the Qasīda

At the heart of Anvari’s reputation lies his unparalleled skill with the qasīda, a poetic form often exceeding a hundred couplets and divided into three parts:

-

Nasīb (Amorous Prelude):

Many of Anvari’s odes open with an evocative scene—dawn’s first light on dew-drenched roses, or the aching memory of a vanished beloved—drawing listeners into an emotional landscape before turning to courtly themes. -

Raḥīl (Journey Description):

He then sweeps us along caravan trails, over desert sands glittering under moonlight, or across snow-capped mountain passes—each image laced with metaphor, foreshadowing the ruler’s steadfastness or the fickleness of fate. -

Madīḥ (Panegyric):

Finally comes the direct praise: the sultan’s battlefield prowess becomes the roar of a lion; his generosity, a spring that quenches all thirst; his justice, a celestial balance holding the world in equipoise.

Anvari’s qasīdas shine with ḥiyal (artful conceit) and badīʿ (ornamental device): conceits so intricate that a single couplet might hinge on a pun, a rare plant’s name, or a mythological allusion. His mastery of metaphor and sound made each ode an event in itself.

The Dark Side of Genius

Yet Anvari’s pen was double-edged. When courtly favor turned, his satire could be merciless:

-

Scathing Epigrams: Under a later patron, he composed terse verses that compared corrupt officials to carrion birds or described courtly intrigues as festering sores.

-

Riddles and Puzzles: He challenged rivals to poetic duels, embedding cryptic wordplay designed to expose any weakness in their learning.

-

Fall from Grace: In his later years, after a shifting political tide and a failed diplomatic mission, Anvari lost his position—legend says he wandered toward India, composing bitter verses that mourned both personal exile and imperial decline.

His fate serves as a reminder: in an age when poetry could crown you or condemn you, the mightiest quill could cut deepest wounds.

Legacy and Influence

Despite the vicissitudes of court life, Anvari’s Dīwān (collected works) was copied and recopied across centuries. His influence rippled through later Persian literature:

-

Stylistic Imprint: Poets such as Niẓāmī and Ḥāfiẓ drew on his lavish imagery and polished rhetoric.

-

Scholarly Commentary: Generations of grammarians and rhetoricians studied his odes to illustrate advanced poetic devices.

-

Cultural Memory: In Iran and beyond, Anvari is taught as the benchmark of panegyric excellence—and warned of as a cautionary tale about pride and patronage.

Conclusion

Anvari’s life and work epitomize the exhilarating—and perilous—exchange between poets and power in medieval Persia. As the celebrated “Prince of Poets,” he raised the qasīda to sublime heights of artistry; as the feared satirist, he reminded his peers that the same art could wound as sharply as a sword. Today, his surviving odes offer modern readers a window into a world where language itself was the greatest treasure—and the greatest danger—of all.