From the pre‑Islamic odes to the ecstatic verses of Sufi mystics, Persian poetry has long revolved around a single, sweeping tension: the pull between earthly love (ʿishq‑e majāzī) and divine love (ʿishq‑e ḥaqīqī). Whether celebrating the beauty of a beloved’s face or yearning for union with the Unseen Beloved, Persian poets weave these two dimensions into a tapestry that illuminates the human heart and its ultimate destiny.

1. Defining the Two Loves

-

Earthly (Majāzī) Love

-

Focuses on the beloved’s physical attributes—wine‑rouged lips, cypress‑like waist, night‑shaded hair.

-

Functions as a metaphor for spiritual longing: the beauty of a human face hints at the beauty of the Divine.

-

Often rendered in ghazal form, with playful wordplay and intricate rhyme.

-

-

Divine (Ḥaqīqī) Love

-

Seeks proximity to, and union with, God.

-

Transcends the sensory world, culminating in fanāʾ (annihilation of the ego) and baqāʾ (subsistence in God).

-

Expressed through allegory, parable, and metaphors drawn from earthly love.

-

2. From Courtly Romance to Mystical Yearning

A. Early Courtly Traditions

Poets like Nizami Ganjavi and Ferdowsi foregrounded majestic heroes and royal romances. In Nizami’s Layla and Majnun, the tragic love of Qays for Layla becomes an emblem of unattainable longing—foreshadowing the mystical readings that would follow.

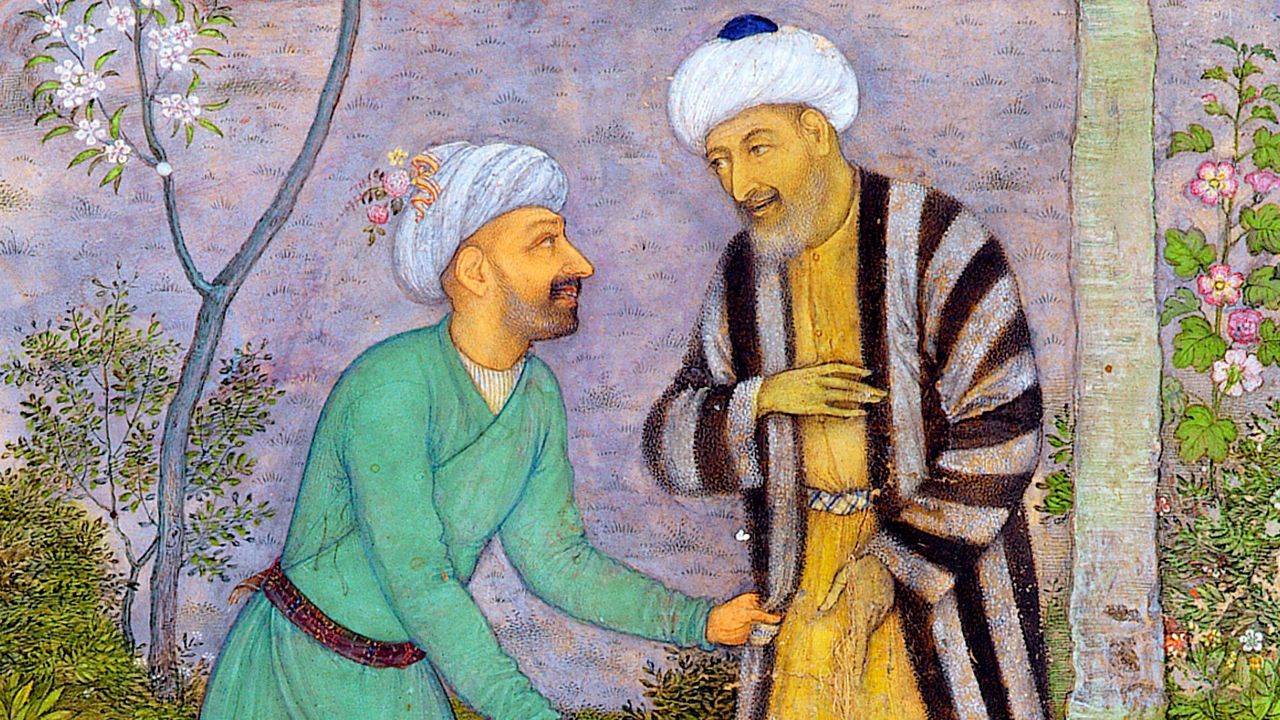

B. The Crossover to Mysticism

By the 12th and 13th centuries, Sufi poets such as Farīd ud‑Dīn ʿAṭṭār, Rūmī, and Saulîḥ of Shiraz began to blur the boundary between earthly and divine love. The human beloved became the “veil” through which the seeker glimpses God’s face:

“The wine of love, though crimson to the eye,

Pours the same ruby essence of the sky.”

― Hafez

3. Major Voices and Their Perspectives

3.1 Rūmī (1207–1273)

-

Opens the Masnavi with the reed‑flute’s lament, mourning separation from its reedbed—an archetype of the soul’s exile from the Divine.

-

Stories of worldly love serve as stepping‑stones: the “moth and flame” warns that the flames of divine love consume all lesser attachments.

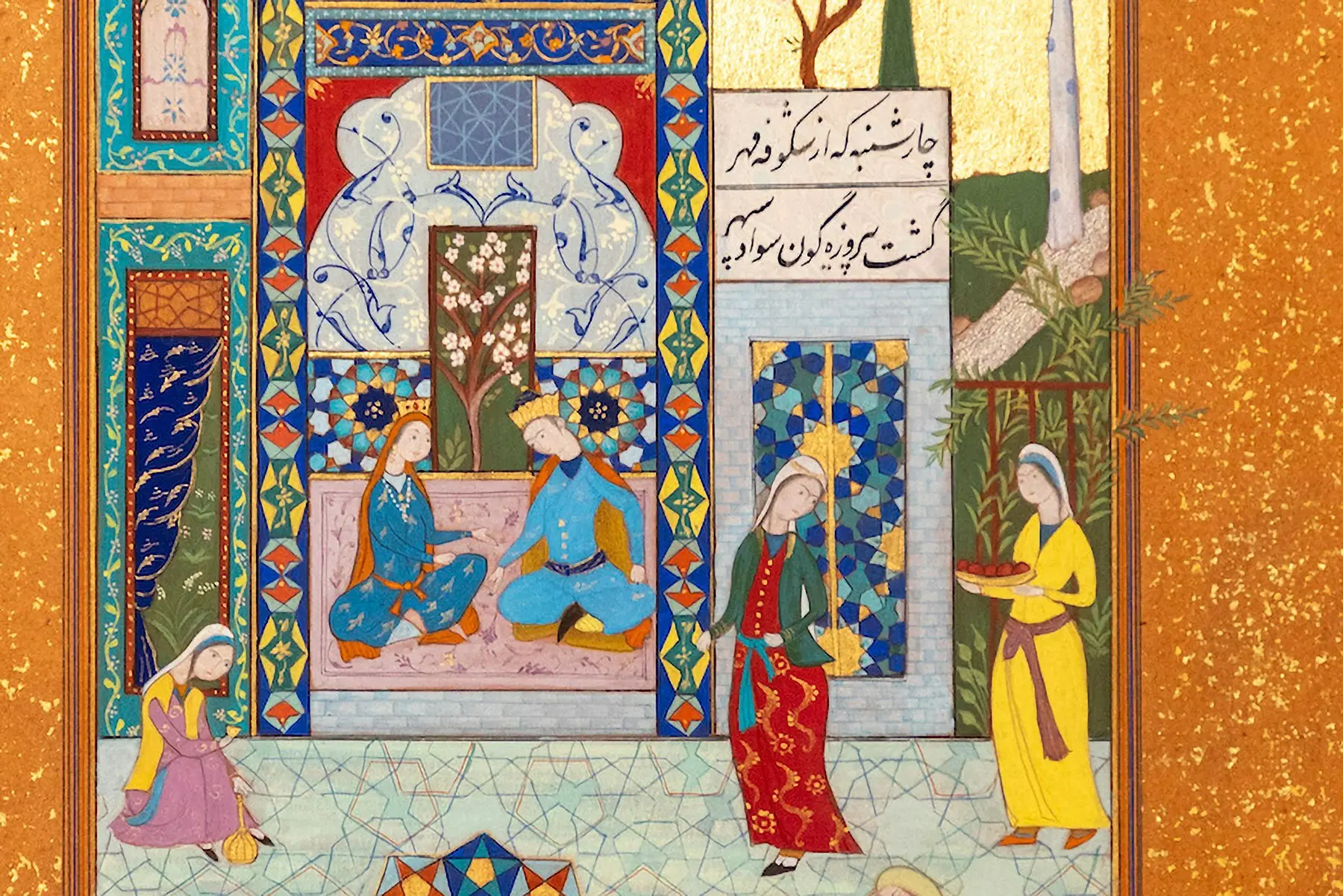

3.2 Hāfez (c. 1315–1390)

-

Master of the ghazal, he layers meanings so that “wine” may be the tavern’s brew and the mystic’s dhikr alike.

-

His poems frequently pivot between indulgent revelry and ecstatic union, inviting readers to taste both glasses.

3.3 Saadi of Shiraz (c. 1210–1291)

-

In Bustan and Golestan, moral tales often end with a quatrain that equates mercy toward humans with mercy from God.

-

Earthly compassion becomes the hallmark of a heart ready for divine embrace.

4. Literary Devices: How Poets Weave the Two Loves

-

Ambiguity and Double Entendre

Words like “wine,” “cup,” and “tavern” oscillate between literal and spiritual readings. -

Paradox and Inversion

The beloved who drains the lover of self becomes the source of ultimate plenitude. -

Symbolic Journeys

From Attar’s Conference of the Birds to Nezami’s Haft Paykar, the quest for a human king or bird transforms into the soul’s search for God.

5. Why This Theme Endures

-

** Universality of Longing:** Whether for romance or transcendence, every heart experiences separation and the hope of reunion.

-

Moral and Spiritual Instruction: Sufi poets taught ethical conduct through the prism of love, making lofty truths accessible.

-

Aesthetic Richness: The interplay of sensual imagery and spiritual insight has inspired countless translations, adaptations, and performances—ensuring Persian poetry’s global resonance.

6. Engaging with Both Loves Today

-

Read Side by Side: Pair a courtly romance (e.g., Layla and Majnun) with a mystical treatise (Masnavi) to trace the evolution of the theme.

-

Reflective Journaling: After reading a ghazal, note which images speak to your human relationships and which stir deeper longings.

-

Creative Practice: Write your own couplet, using a familiar motif—like the rose or the nightingale—to express both earthly and divine yearnings.

Conclusion

In Persian poetry, the dance between earthly and divine love is not an either/or but a both/and: the human beloved points the way to the Beloved Beyond Names. Through layers of metaphor, paradox, and storytelling, poets invite us to taste life’s sweetness and then transcend it—guiding every reader from the rose’s fragrance to the rose of eternity.