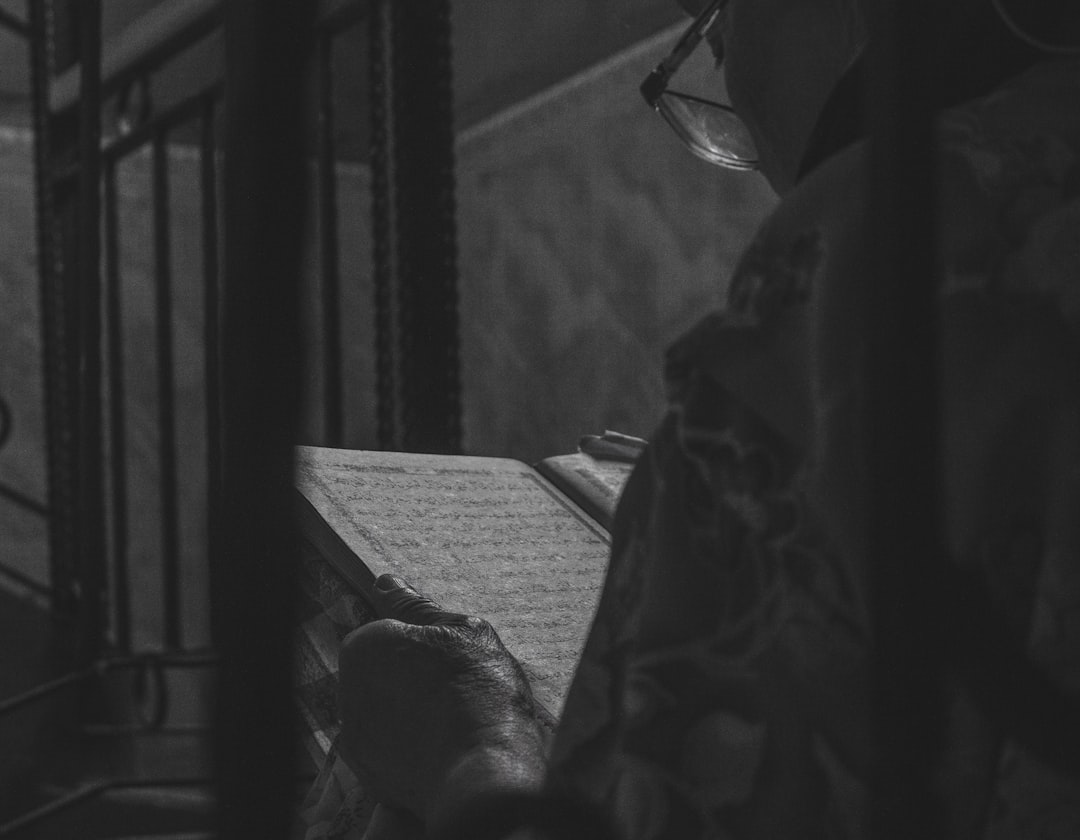

Long before the arrival of Islam, the lands of ancient Iran were shaped by the hymns and myths of Zoroaster’s followers, preserved in the sacred verses of the Avesta. When later poets wove their grand epics—above all, Ferdowsī’s Shāhnāmeh—they carried forward faint yet unmistakable traces of that pre-Islamic heritage. In this post, we’ll follow the breadcrumbs from the Avesta’s cosmic vision into Persia’s medieval storytelling tradition.

1. The Avesta’s Vision: A Cosmic Drama

The Avesta—the holy book of Zoroastrianism—lays out a world governed by two primal forces:

-

Ahura Mazda, the Wise Lord who embodies truth (asha) and life

-

Angra Mainyu (Ahriman), the spirit of deceit and decay

Its hymns celebrate the first creatures, the archetypal king Yima (later Jamshīd), and the promise of a golden age. Though the Avesta survives only in fragmentary form, its dualistic cosmology and lofty ideals of justice and divine glory (farr, or khvarnah) ran deep in Iranian lore.

2. From Pahlavi Chronicles to New Persian Verse

Between the Avesta and the great Persian epics lay centuries of Middle Persian (Pahlavi) writings—court histories, royal biographies, and short epic tales like the Āyādgār-i Zarīrān. These works, often penned in Sassanian fire-temple circles, transmitted mythic names (Jamshīd, Zāl, Rostam) and motifs (the simurgh, the farr-bestowing bird) into the medieval imagination.

When Ferdowsī set out to compose his Shāhnāmeh (late 10th–early 11th century), he drew on these Pahlavi sources—now largely lost—alongside oral traditions. His stated aim was to “restore the Iranians’ ancient glory,” painstakingly re-Hellenizing Arabicized names back into their old Iranian forms.

3. Jamshīd’s Golden Reign and Zahhāk’s Dark Legacy

Two of the Shāhnāmeh’s opening episodes feel like direct adaptations of Avesta lore:

-

Jamshīd (Yima)

-

In the Avesta, Yima rules in a world of limitless abundance, raising a “varena” or enclosure to protect creatures through the first winter.

-

Ferdowsī’s Jamshīd fashions divine crowns, subdues demons, and shapes the festival of Nowruz—portrayed as the high point of human civilization before hubris sets in.

-

-

Zahhāk (Aži Dahāka)

-

Aži Dahāka, the three-headed dragon-demon in the Gāthās, becomes Zahhāk, the tyrant whose shoulder serpents demand human brains.

-

This monstrous king, whose reign casts shadows over the land, vividly evokes the cosmic threat of Ahriman’s reign of chaos.

-

4. The Simurgh and the Divine Spark (Farr)

One of the most iconic Avesta echoes is the simurgh—a great, wise bird associated with divine favor. In the Shāhnāmeh:

-

Zāl’s Upbringing

-

Abandoned for his white hair, the infant Zāl is raised by the simurgh in the Alborz mountains.

-

The bird’s feathers later save Rostam’s life in battle—symbolizing the transmission of farr, the kingly aura granted by heaven.

-

This image of a supernatural protector bird reaches back to Zoroastrian images of the radiant bird tied to Ahura Mazda’s court.

5. Asha, Arta, and the Heroic Ethos

Beyond names and creatures, Persian epics retain moral and cosmological concepts from the Avesta:

-

Asha (Truth, Right Order)

-

Heroes like Rostam stand for the cosmic order—fighting injustice, protecting the weak, and upholding oaths.

-

-

Khvarnah (Divine Glory)

-

The rise and fall of dynasties turns on possession of the farr: good kings are bathed in its light, corrupt ones lose it and invite disaster.

-

These underlying principles give epic battles a deeper resonance: they’re not just political struggles but enactments of the universe’s moral drama.

6. Beyond the Shāhnāmeh: Later Ripples

Ferdowsī’s model inspired subsequent epics and narratives that subtly echoed pre-Islamic lore:

-

Nizami’s Khosrow and Shirin: While primarily a romantic tale, it casts its Sassanian hero Khosrow Parviz as a figure heir to Jamshīd’s legacy, grappling with the burdens of divine right.

-

Local Traditions: Regional storytellers retained folk-tales of Yima’s vanished treasures, of magic gems (xoršēd), and of the “old good days” when kings ruled by the light of asha.

7. Why It Matters Today

-

Cultural Continuity: Recognizing Avesta traces in Persian epics reminds us that Iranian identity spans beyond any single religion or dynasty.

-

Mythic Depth: Those ancient Zoroastrian motifs—cosmic struggle, divine favor, sacred kingship—still resonate in modern art, literature, and festivals like Nowruz.

-

Literary Inspiration: Contemporary writers and filmmakers draw on these layered origins to craft new stories that echo the world’s oldest epic traditions.

“In every rustling leaf of the simurgh’s tree, you hear the hymn of creation—and the promise that truth shall rise again.”

By tracing the Avesta’s faint yet vital echoes in Persian epics, we glimpse a thousand-year conversation between sacred hymn and heroic romance—one that continues to shape the Persian literary imagination.