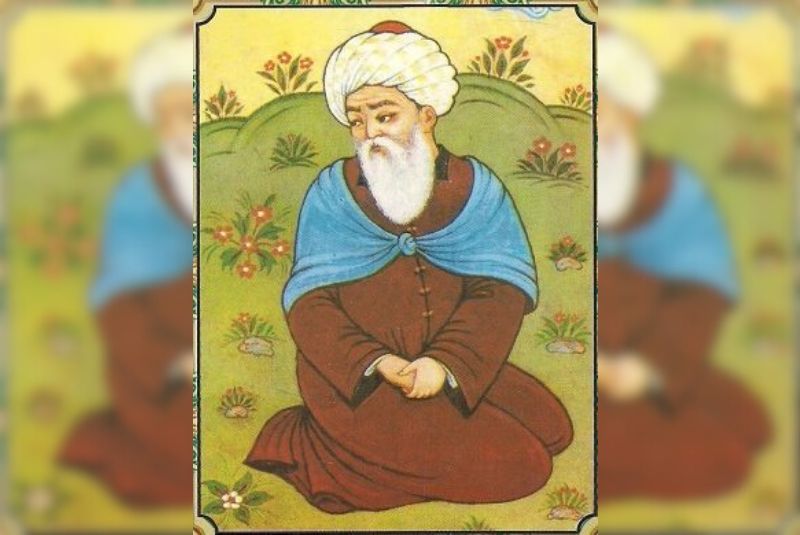

In the panorama of Persian literature, few figures stand as tall—or as gracefully—as Nur ad‑Dīn Abd ar‑Raḥmān Jāmī (1414–1492 CE). Celebrated as the “Last Great Classical Poet of Persia,” Jami’s prodigious output spanned mystical epics, prose treatises, devotional odes, and pithy quatrains. His work represents the culmination of centuries of Persian–Sufi synthesis, bridging the world of medieval Sufism with the early stirrings of the modern era.

1. A Life at the Crossroads of Learning

Born in the city of Jam (in modern-day Afghanistan), Jami moved early to the scholarly centers of Herat and Shiraz, both vibrant hubs under the Timurid princes. His education combined:

-

Scriptural Mastery: Deep study of the Quran, hadith, and Islamic jurisprudence.

-

Sufi Initiation: Apprenticeship under masters of the Naqshbandī and Kubrawī orders, fostering a lifelong devotion to spiritual practice.

-

Literary Acumen: Exposure to the full sweep of Persian poetry—from Rudaki through Rumi and Saadi—paving the way for his own creative flowering.

Over eight decades, Jami cultivated friendships with courtiers, theologians, and fellow poets, securing patronage but also preserving the independence to speak truth in verse and prose.

2. Major Works: From Epic Romance to Devotional Treatise

A. Haft Awrang (“Seven Thrones”)

-

Form: A masnavi collection of seven narrative poems, each dedicated to a different Timurid patron.

-

Themes: Courtly romance, morality, mystical allegory.

-

Highlights:

-

Yusuf and Zulaikha: The Qur’anic love story recast as a soul’s longing for union with the Divine Beloved.

-

Layla and Majnun: Majnun’s descent into ecstatic madness as the heart’s path to realization.

-

The Haft Awrang stands as Jami’s magnum opus—6000+ couplets of polished meter, rich symbolism, and subtle ethical counsel.

B. Bahāristān (“The Spring Garden”)

-

Form: Prose interspersed with quatrains, modeled on Saadi’s Golestan.

-

Content: Seven “days” of moral tales—on generosity, contentment, justice, and repentance.

-

Purpose: A moral handbook for both rulers and commoners, blending entertainment with instruction.

C. Lawa’ih (“Glimpses”)

-

Form: A short, personal treatise on Sufi practice.

-

Focus: Practical guidance on dhikr (remembrance), meditation, and the ethics of the spiritual path.

-

Tone: Intimate, direct—Jami’s voice as mentor speaking to disciples.

D. Quatrains and Ghazals

Beyond his longer compositions, Jami crafted hundreds of rubā‘ī and ghazals, each a distilled moment of insight—on divine love, the dance of fate, or the mirror of the heart.

3. Thematic Threads: Unity, Love, and Ethical Action

Across Jami’s oeuvre, three interwoven themes emerge:

-

Unity of Being (Wahdat al‑Wujūd): Building on Ibn ʿArabī and earlier mystics, Jami celebrates the oneness underlying creation—while acknowledging the play of divine names in multiplicity.

-

Love as Path: Whether in epic romance or devotional verse, love—romantic, fraternal, or mystical—is the force that drives the seeker from separation to reunion.

-

Ethics in Spirituality: True mysticism for Jami is inseparable from justice, compassion, and service. His moral tales in Bahāristān remind readers that inner illumination must manifest in right action.

4. Jami’s Style: Elegance and Eloquence

Jami’s hallmark is a balance of polish and warmth:

-

Linguistic Mastery: His Persian is refined yet accessible, full of rhythmic cadences that lend themselves to recitation and song.

-

Imagery: Gardens, wine, candlelight, and the rose-nightingale motif recur as symbols of spiritual beauty and longing.

-

Tone: Equally at home addressing princes or pilgrims, Jami’s voice can be lofty one moment and playfully intimate the next.

His ability to shift register—courtly panegyric, storyteller’s charm, dervish’s counsel—makes his writing endlessly engaging.

5. Legacy: A Bridge to the Modern World

As the last great classical poet, Jami marks a transition:

-

End of an Era: After Jami, the apex of Persian–Sufi poetic synthesis gives way to changing tastes, new literary forms, and the influences of rising regional powers.

-

Enduring Influence: His works remained central reading in Persianate societies—recited in literary circles, taught in madrasas, and admired by later luminaries like Saib Tabrizi and Nushirwan Pāshā.

-

Global Reach: Translations of the Haft Awrang and Jami’s quatrains have introduced his thought to new audiences, influencing Ottoman poets in Turkey, Mughal writers in India, and modern scholars worldwide.

Conclusion: The Eternal Spring of Jami’s Verse

Nur ad‑Din Jami’s life and poetry epitomize the “spring garden” he so often described—a place where beauty, wisdom, and devotion bloom together. As the last great classical poet of Persia, he wove together the threads of mysticism, romance, and moral reflection into a tapestry that still enchants and instructs. For readers seeking the heart of Persian–Sufi literature, Jami’s works offer an eternal source of inspiration—a reminder that through love, unity, and right action, the soul’s journey finds its fullest expression.