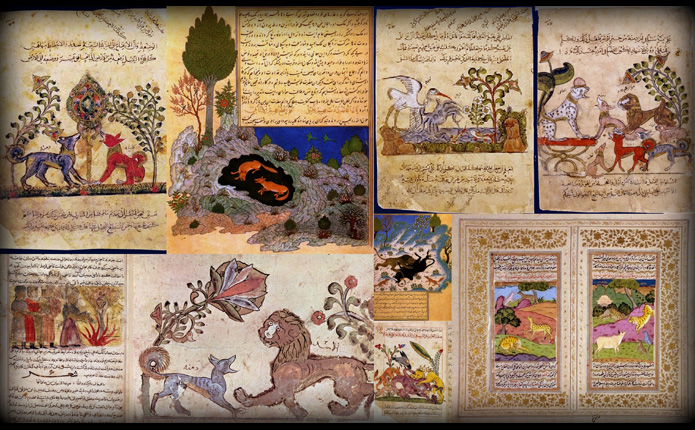

Few works of world literature have traveled as far or taught as timelessly as Kalīla wa Dimna. Originating in ancient India as the Pañcatantra, this collection of animal fables was translated into Pahlavi in the 6th century CE, then into Arabic by Ibn al‑Muqaffaʿ in the 8th century, and from there into Persian—where it flourished as Kalīla wa Dimna. Over the centuries, its clever stories have guided princes, ministers, and readers of every station toward wise and ethical conduct.

1. A Tale of Two Jackals: Structure and Origins

-

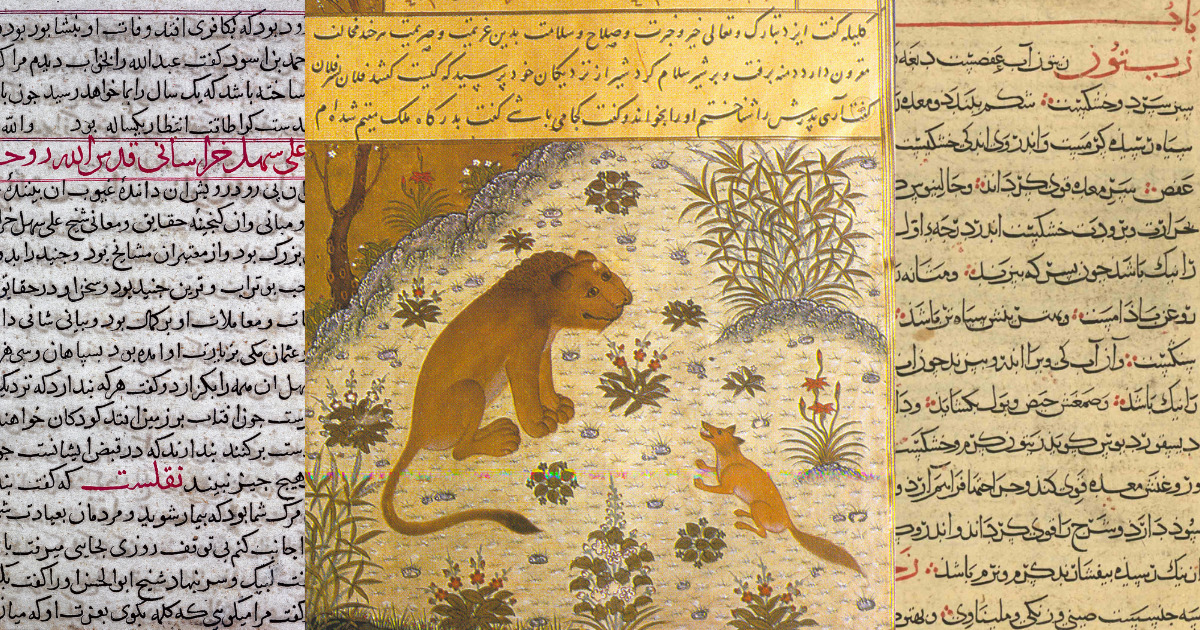

The Frame Narrative. A lion‑king, Dabsūrah, falls ill. His minister, the bull Shanzabeh, tells him stories—first of Kalīla and Dimna (two jackals), then of other beasts—to instruct him in just and prudent rule.

-

Animal Allegory. By assigning human virtues and vices to familiar creatures—lions, bulls, birds, foxes—the book offers both entertaining drama and pointed moral critique.

-

Layered Transmissions. From Sanskrit → Pahlavi (Burzōē) → Arabic (Ibn al‑Muqaffaʿ) → Persian (various translators from the 11th century onward), each version added local color while preserving core wisdom.

2. Key Moral Themes

A. Cunning and Consequence

-

Kalīla vs. Dimna. Dimna’s ambition drives him to plot against the bull Shanzabeh—teaching that unchecked ambition and deceit lead to downfall.

-

Lesson: Intelligent counsel must be tempered by integrity; manipulative schemers may rise temporarily but eventual collapse awaits.

B. Wise Leadership

-

The Lion‑King’s Woes. Dabsūrah learns that justice, consultation, and temperance sustain a realm; tyranny and rashness invite rebellion.

-

Lesson: A ruler’s legitimacy rests on fairness and listening to sound advice, not on fear alone.

C. Friendship and Betrayal

-

Animal Alliances. Allies like the crow and the owl model loyalty; others turn opportunistic when fortunes shift.

-

Lesson: Choose confidants carefully; true friends advise for your good, not their gain.

D. Balance of Strength and Compassion

-

Fox and Crane, Turtle and Geese. Stories of hosts and guests underscore reciprocity: generosity earns gratitude, cruelty breeds enmity.

-

Lesson: Power without mercy corrodes social bonds; compassion ensures stability and goodwill.

3. Literary Style and Rhetoric

-

Concise Episodes. Each fable is a self‑contained narrative, ideal for memorization and recitation at court or in madrasa.

-

Embedded Couplets. Persian redactions often insert rubā‘ī (quatrains) to distill the moral in a memorable, lyrical form.

-

Dialogic Format. Frequent dialogues keep the pace lively, turning abstract maxims into dramatic exchanges.

4. Historical Impact and Legacy

-

Courtly Education. For centuries, Kalīla wa Dimna was part of the princely curriculum—teaching young heirs the art of statecraft through story.

-

Cultural Bridges. Its translations into Greek, Hebrew, Georgian, and European languages helped transmit Eastern wisdom to the West.

-

Modern Resonance. Contemporary anthologies, children’s editions, and even animated adaptations keep these fables alive—reminding us that human nature remains much the same.

5. Reading and Reflecting Today

-

Spot the Archetypes. Notice how each animal embodies recognizable traits (the sly fox, the proud peacock)—and how you see them reflected in modern figures.

-

Journal the Morals. After reading an episode, jot down how its lesson applies to a current workplace, political, or personal situation.

-

Share the Stories. Host a storytelling circle—invite friends to read a fable aloud and discuss its relevance, as courts once did centuries ago.

Conclusion

Kalīla wa Dimna endures because it speaks to universal truths through engaging stories. Whether advising a medieval sultan or guiding a modern manager, its fables reveal that wisdom often comes wrapped in humor, drama, and the unexpected antics of animals. In every sly fox and noble lion, we find mirrors of ourselves—reminding us that, no matter how complex our world grows, the core lessons of ethics and leadership remain forever relevant.