Persian poetry, rich with mysticism, beauty, and philosophical insight, has long served as a mirror reflecting the deepest truths of human existence. Among its most enduring and haunting themes are life, death, and the relentless passage of time. From the epics of Ferdowsi to the melancholic quatrains of Khayyam, Persian poets have asked the same timeless questions: What does it mean to live well? What awaits after death? How do we reconcile the brevity of life with the longing for meaning?

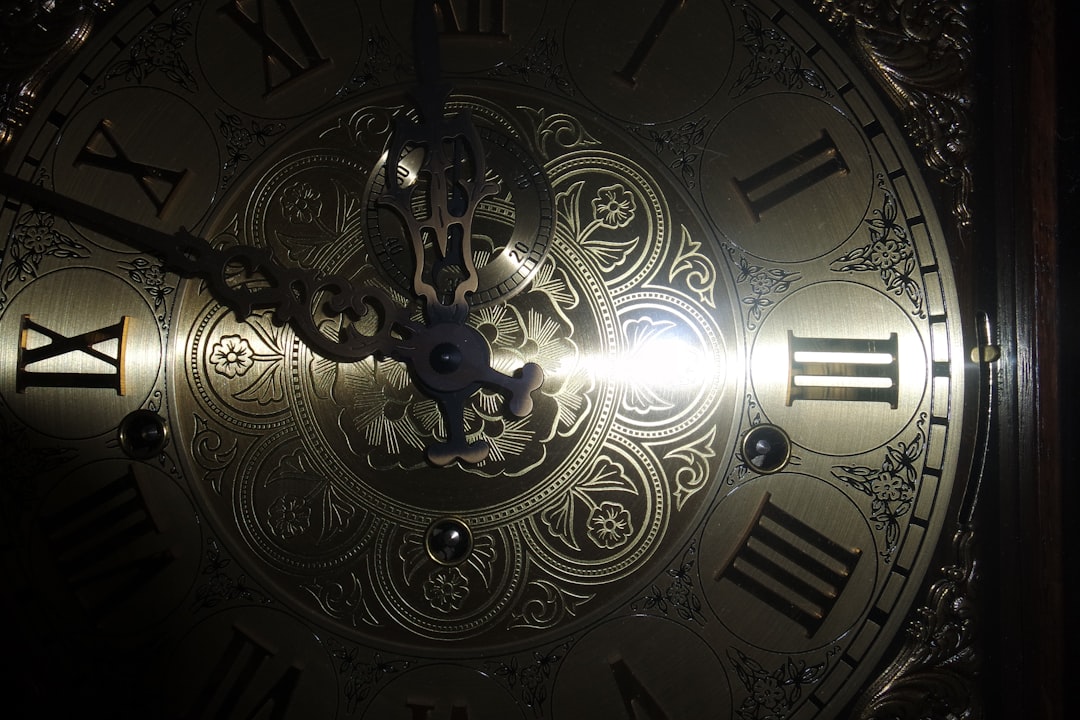

The Dance of Time: Fleeting Moments and Eternal Questions

Time in Persian verse is both an enemy and a muse. It flows like a river—beautiful, powerful, and indifferent.

“This world is a caravanserai—a night's stop and gone.

Life, a shadow that flits across the wall.”

— Omar Khayyam

Khayyam, perhaps more than any other poet, voiced the existential anxiety of time’s passing. In his Rubaiyat, time mocks human ambition, topples kings and beggars alike, and teaches us to drink wine and seize the now—carpe diem, Persian-style.

But this isn't hedonism. Rather, it's a philosophical resignation to impermanence. The world is transient, so value the moment and be mindful of what truly matters.

Life as a Test, a Journey, and a Dream

In Islamic-Persian cosmology, life is often portrayed as a test—a temporary realm through which the soul must journey toward the Divine. This view finds eloquent expression in Rumi’s Masnavi:

“This world is a mountain, and your actions the shout;

The echo returns to you in due time.”

For Rumi and the Sufis, life is a school of the soul. Its pains and pleasures, its victories and losses, are all signs guiding the seeker toward higher truth. Even death is not an end, but a transformation—the soul shedding the cage of the body to return to its origin.

“Why should I fear death? When I die,

I will soar with angels and speak to the stars.”

— Rumi

Death: An Invitation to Reflect

Persian poets don't shy away from death—they speak to it, walk with it, and invite readers to contemplate its certainty. Saadi, known for his wisdom and moderation, writes in the Golestan:

“The remembrance of death is the polish of the heart.”

This line reflects a long-standing belief in Persian and Islamic ethics: that death, when remembered sincerely, purifies the soul. It sobers desire, humbles pride, and kindles compassion.

But death in Persian poetry is not just solemn—it can also be romanticized. In the love poetry of Hafez, death often becomes union—not loss, but the soul’s melting into the Beloved.

“I am the bird of the celestial sphere, not of this world of dust;

For a few days in a cage of grief, I made my nest.”

Hafez's mysticism transforms death into transcendence—a return to the eternal winehouse, to love without form or end.

The Garden of Being: Nature and Mortality

Persian poets often use natural imagery—gardens, flowers, seasons—to meditate on life and death. Spring becomes a metaphor for youthful beauty, quickly fading. The rose blooms and withers in the same breath, teaching that what is most beautiful is also most impermanent.

“Spring has come, and again the rose is born.

But where are the friends who have seen last spring?”

— Khayyam

The cyclical rhythm of nature becomes a metaphor for the soul’s journey through life, death, and rebirth. It’s a reminder that all is passing, yet nothing is truly lost.

Conclusion: Mortality as Meaning

In Persian poetry, mortality is not merely mourned—it is confronted, transformed, and even celebrated. Whether through the quiet resignation of Khayyam, the divine yearning of Rumi, or the worldly reflections of Saadi and Hafez, the poets invite us to see death not as the end, but as a mirror to life.

To contemplate death is to ask: What matters? What remains when all else falls away?

In doing so, Persian poetry offers not despair, but clarity. In the shadow of death, we find the light of meaning. And in the face of time’s passage, we are taught to live—not endlessly, but intentionally.