Introduction

In the rich tapestry of classical Persian literature, Manuchehri Damghani (fl. mid-11th century) stands out as a master of tightly woven stanzaic poetry and vivid nature descriptions. Celebrated for his elegant qasīdas (panegyric odes) and ingenious mathnawī stanzas, Manuchehri brought the beauties of the natural world—garden blooms, migrating birds, shifting seasons—into sharp, sensuous focus. In this post, we’ll explore his life at the Ghaznavid court, unpack his signature poetic forms, dive into his lush nature imagery, and consider why his verses continue to inspire readers and writers today.

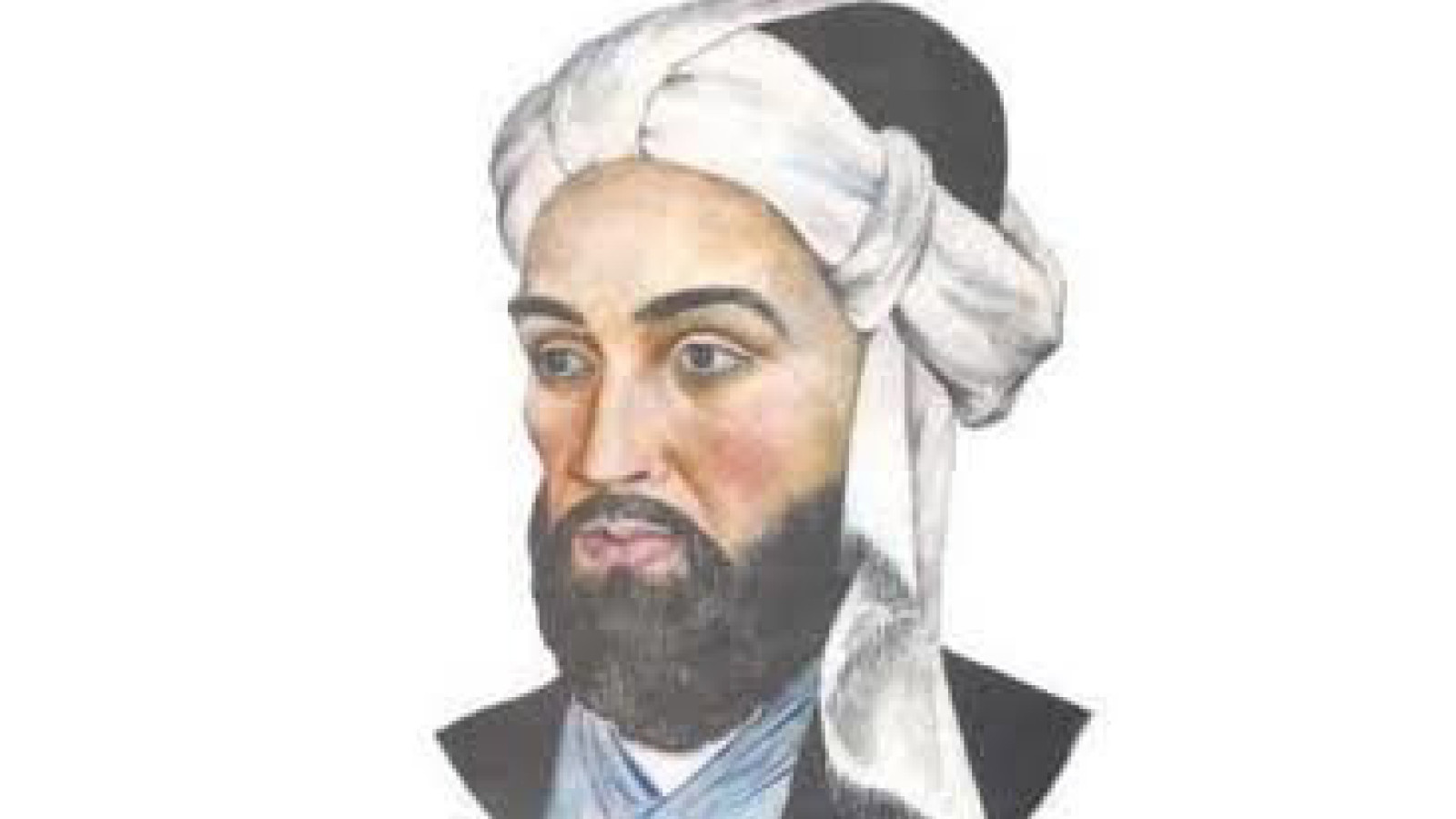

Life and Courtly Context

Born in the town of Damghan (hence his nisba “Damghani”), Manuchehri’s exact birth and death dates are uncertain, but his career flourished under Sultan Masʿūd I of Ghazni (r. 1030–1041 CE). The Ghaznavid court prized eloquence and learning, and Manuchehri earned the honorific Amīr al-Shuʿarāʾ (“Prince of Poets”) for his ability to compose dazzling panegyrics on demand.

His patrons included high-ranking military commanders and provincial governors, whose victories, hospitality, and piety he immortalized in verse. Yet even as he celebrated human achievement, Manuchehri’s true genius lay in his capacity to frame that praise within the rhythms and textures of the natural world.

Innovation in Stanzaic Forms

While many of his predecessors favored the single-threaded qasīda or the sprawling masnavī, Manuchehri excelled at stanzaic forms—poems built from repeating, self-contained stanzas that each offer a complete image or thought. Two forms he particularly mastered are:

-

Rubaʿī (Quatrains).

Four-line stanzas with a tight rhyme scheme (AABA), used both for standalone epigrams and as refrains within larger odes. His rubaʿīs often capture a single moment—“the nightingale’s breast ablaze at dawn,” or “petals drifting on a silent stream”—with poignant simplicity. -

Mathnawī (Rhymed Couplets in Stanzas).

Unlike epic mathnawīs that unfold long narratives, Manuchehri’s mathnawī stanzas are concise cycles of couplets, each cycle returning to a recurring refrain or image. This structure creates a musical echo, as though the reader is circling a garden path and discovering new blossoms at every turn.

By alternating rich description with rhythmic refrains, Manuchehri turned each poem into a miniature soundscape—where meter, rhyme, and imagery harmonize.

The Poetry of Gardens and Skies

Nature isn’t mere decoration in Manuchehri’s work; it provides the very language through which he speaks of power, emotion, and divine grace. Three recurring motifs illustrate his approach:

-

Floral Metaphors.

Roses, jasmine, narcissus, and tulips appear not only as symbols of beauty but also as living characters:“A scarlet rose unfurls her velvet tongue,

Whispering secrets to the silver moth at night.”

Here, the rose’s bloom parallels a ruler’s eloquence, while the moth’s flutter suggests the poet’s own eager devotion. -

Seasonal Transitions.

Manuchehri marks political cycles and personal fortunes by the turn of the seasons: spring’s first breeze heralds a new reign, autumn’s withered leaves forewarn of a commander’s fall. His odes often begin with a taṣṣīb (nature introduction) that sets the emotional tone before moving to panegyric. -

Celestial Imagery.

Stars, constellations, and the changing moon provide cosmic perspective. In one famous stanza, the sovereign’s just rule is likened to the midnight sky—unchanging amid swirling clouds:“As Atlas bears the heavens on his shoulders,

So does his justice hold a world in balance.”

Sample Excerpt

Below is a translated excerpt from one of Manuchehri’s rubaʿī stanzas, capturing his blend of courtly praise and natural observation:

“The garden quakes at dawn with orchard blooms,

As royal banners stir the saffron breeze;

Between the rose’s blush and falcon’s cry,

We glimpse the ruler’s grace on earth and skies.”

Here, garden and court are inseparable: the flower’s color echoes embroidered flags, and the falcon’s flight parallels the eagle-eyed intellect of the sultan.

Enduring Influence

Manuchehri’s tight stanzas and vivid imagery left a lasting mark on Persian poetics:

-

Refinement of Rubaʿī. His quatrains prefigure the later brilliance of Omar Khayyām and Khāqānī, who took the form into philosophical and mystical realms.

-

Strophic Resonance. Modern scholars credit him with showing how recurring refrains can build poetic momentum—an influence seen in later lyrical traditions.

-

Nature as Symbol and Sensation. By treating natural elements as both metaphor and living presence, Manuchehri set a precedent for garden symbolism that flourished in Safavid miniatures and Mughal poetry.

Conclusion

Manuchehri Damghani’s genius lies in his ability to distill the grandeur of human achievement into stanzas that breathe with petals, winds, and starlight. His poems remind us that the greatest panegyric is not merely a litany of praises but a living tapestry woven from the textures of the world itself. For today’s poets and readers, Manuchehri offers a lesson in precision, musicality, and the enduring power of nature to shape our most exalted words.