Ancient Persia, a land renowned for its rich history and vibrant culture, possessed a calendar punctuated by numerous significant occasions. These were not merely arbitrary dates but rather deeply meaningful events intricately woven with the threads of Zoroastrianism, the dominant faith of the time, and the essential agricultural cycles that dictated the rhythm of life for its people. From grand, multi-day festivals to more frequent monthly observances, these occasions served as vital expressions of their spiritual beliefs, their connection to the natural world, and their strong sense of community. This post lists the historical context, rituals, symbolism, and modern-day relevance of these old Persian traditions, revealing a profound and enduring legacy.

The Intertwined Pillars: Zoroastrianism and the Agricultural World of Ancient Persia

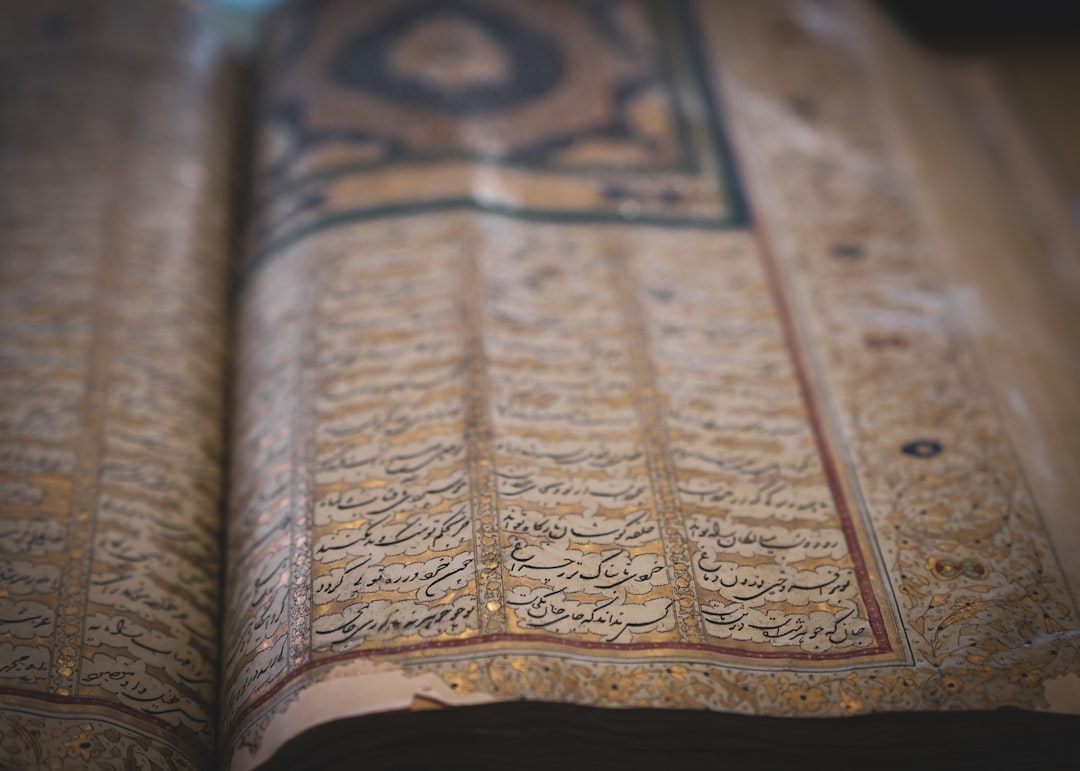

The bedrock upon which many old Persian occasions were built was Zoroastrianism. Emerging around the 6th century BCE through the teachings of the prophet Zoroaster (also known as Zarathustra), this faith rapidly gained prominence, becoming the official religion of ancient Persia by 650 BCE. Zoroastrianism, considered one of the oldest monotheistic religions, although containing dualistic elements, centered on the worship of Ahura Mazda, the supreme creator, and the ongoing cosmic struggle against Angra Mainyu, the embodiment of evil. This fundamental duality of good and evil, light and darkness, profoundly influenced Persian thought and was often reflected in their celebrations. The sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, most notably the Avesta, encompassing hymns (Gathas), liturgical texts (Yasna), and purity rituals (Vendidad), provided the framework for their religious practices and moral code, which emphasized "good thoughts, good words, and good deeds". Fire held a central position in Zoroastrianism as a symbol of truth, light, and the presence of Ahura Mazda, leading to the establishment of fire temples as places of worship.

A core concept within Zoroastrianism that significantly shaped their understanding of the world and their celebrations was Asha. Representing truth, righteousness, cosmic order, and divine law, Asha was intrinsically linked to fire and served as a guiding principle for ethical conduct. It stood in opposition to Druj, representing falsehood and deceit, and maintaining harmony and balance within the universe was seen as essential. Living in accordance with Asha was therefore crucial for aligning oneself with the will of Ahura Mazda. This emphasis on order and truth likely extended to their understanding of the natural world, including the predictable cycles of agriculture.

Ancient Persian society was fundamentally agrarian. The success of their harvests directly determined their survival and prosperity, making their lives deeply connected to the changing seasons and the annual cycle of planting, growth, and harvest. Zoroastrian teachings even influenced their land management practices, leading to the development of sophisticated irrigation systems. Given this profound dependence on agriculture, their religious beliefs and practices naturally intertwined with the vital need to ensure favorable conditions for farming and to celebrate the bounty of the land. Their festivals, therefore, often served a dual purpose: religious observance and marking crucial points in the agricultural calendar.

It is important to acknowledge that Zoroastrianism did not emerge in a vacuum. It evolved from earlier polytheistic Persian religions where nature gods, such as those associated with water and fire, were worshipped, and the concept of a cosmic struggle between good and evil already existed. Some of these pre-Zoroastrian traditions and deities were subsequently incorporated or reinterpreted within the Zoroastrian framework, providing a deeper historical context for understanding the rituals and symbolism of later festivals.

Major Occasions: Milestones in the Persian Year

Several major occasions stood out in the old Persian calendar, each holding unique significance rooted in their faith and agricultural practices.

Nowruz (نوروز): The Spring Equinox and New Beginnings

Nowruz, literally meaning "New Day," marks the Persian New Year and coincides with the spring equinox, typically around March 20th or 21st. This most significant of Persian festivals, celebrated for approximately two weeks, has deep roots in both Zoroastrianism and pre-Zoroastrian traditions, symbolizing the triumph of good over evil and the renewal of nature. Historical records suggest that Nowruz was celebrated as far back as the Achaemenid Empire (550-330 BCE) in Persepolis. In Zoroastrian tradition, Nowruz is linked to the return of Rapithwin, the personification of summer and noon. Mythological origins also attribute its inception to the legendary King Jamshid in the epic Shahnameh. The enduring presence of Nowruz throughout Persian history underscores its fundamental importance to Persian identity, transcending religious and political shifts across millennia.

The celebrations of Nowruz are rich with specific rituals and customs. Khaneh Tekani, the thorough spring cleaning of homes, symbolizes a fresh start to the new year. A central tradition is the setting of the Haft-Seen table, featuring seven symbolic items whose names begin with the Persian letter "Seen" (س). These items include Sabzeh (sprouts) representing rebirth and growth, Samanu (sweet wheat pudding) symbolizing power and strength, Senjed (oleaster) signifying love and wisdom, Seeb (apple) for beauty and health, Sir (garlic) for health and protection, Serkeh (vinegar) representing age and patience, and Somaq (sumac) symbolizing sunrise and the victory of light over darkness. Other symbolic items like a mirror, candles, painted eggs, goldfish, and a holy book are also commonly included. Social connections are renewed through Did o Bazdid, visits to relatives and friends, and elders bestow gifts, known as Eidi, upon younger family members. On the thirteenth day after Nowruz, people partake in Sizdah Bedar, spending the day outdoors in nature, picnicking, and releasing the Sabzeh into flowing water to ward off bad luck. The eve of the last Wednesday before Nowruz is marked by Chaharshanbe Suri, a fire festival where people jump over bonfires, chanting "Sorkhi-ye to az man, zardi-ye man az to" (Your redness is mine, my paleness is yours), symbolizing purification and welcoming the new year with warmth and light. The intricate rituals of Nowruz, particularly the symbolic significance of the Haft-Seen items, reveal a sophisticated belief system where everyday objects embody deeper meanings related to hopes and aspirations for the coming year.

The symbolism inherent in Nowruz encompasses the core tenets of Zoroastrianism and the practicalities of an agricultural society. It represents the triumph of good over evil and light over darkness, the renewal of nature, and the beginning of spring. The fire rituals of Chaharshanbe Suri signify purification and cleansing, while the various traditions express hope for prosperity, health, love, and happiness in the year ahead. Fundamentally, Nowruz marks the start of the growing season, embodying the anticipation of a bountiful harvest and the deep connection to the agricultural cycles that sustained their lives. The festival's seamless blend of Zoroastrian cosmology with the practical concerns of agriculture underscores the interconnectedness of their spiritual and material existence.

Yalda Night (شب یلدا) or Shab-e Chelleh (شب چله): Celebrating the Sun's Rebirth

Yalda Night, also known as Shab-e Chelleh, is celebrated on the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, typically around December 20th or 21st. This ancient festival marks the "rebirth of the sun" and the victory of light over darkness. Its origins trace back to ancient Persia and Zoroastrian traditions, potentially even earlier. The term "Yalda" itself has Syriac origins, meaning "birth," possibly reflecting early cultural exchanges. In ancient times, this longest night was considered inauspicious, a time when evil forces were thought to be at their strongest, prompting people to stay awake and ward them off.

The rituals and customs of Yalda Night center around family and community. Families gather, often at the home of the eldest member, and stay up late into the night. Special foods are prepared and enjoyed, particularly red fruits like watermelon and pomegranates, symbolizing fertility and the sun, along with nuts and dried fruits. A significant tradition involves reading poetry, especially from the Divan-e Hafez, often used for divination. Storytelling and simply enjoying the company of loved ones are also central to the celebration. The practice of lighting candles or fires echoes ancient customs intended to ward off evil during the long night. The emphasis on red-colored foods during Yalda Night likely connects to the symbolism of dawn and the anticipation of the sun's return, reinforcing the theme of light overcoming darkness.

The symbolic meanings of Yalda Night are deeply rooted in Zoroastrian beliefs and the natural cycle of the seasons. It signifies the victory of light over darkness and the rebirth of the sun, marking the beginning of longer days. The foods consumed symbolize fertility and abundance, while the gathering of family and friends strengthens communal bonds. Marking the darkest time before the return of longer days, Yalda Night holds significance in the agricultural calendar, signaling the eventual arrival of spring. This celebration serves as a powerful reminder of hope and resilience during the darkest period of the year, reflecting a deep understanding of natural cycles and their impact on human emotions.

Mehregan (مهرگان): Celebrating Friendship and Covenant

Mehregan was a significant festival dedicated to Mithra, the Zoroastrian angel of friendship, covenant, and light. Celebrated around the autumnal equinox, approximately on October 2nd [initial query], Mehregan emphasized thanksgiving, love, friendship, and the strengthening of social bonds [initial query]. Mithra's importance predates Zoroastrianism, indicating a continuity of reverence for this deity. The dedication of a major festival to Mithra, a figure significant in both Zoroastrian and pre-Zoroastrian traditions, illustrates the syncretic nature of Persian religious beliefs.

The customs associated with Mehregan included wearing new clothes, symbolizing renewal and celebration, and the exchange of gifts as tokens of affection and commitment [initial query]. Feasts were held, highlighting the abundance of the harvest season [initial query]. These practices of wearing new attire and exchanging gifts echo similar traditions in other autumnal harvest festivals across the globe, suggesting a universal human inclination to celebrate the land's bounty.

The symbolism of Mehregan centered on honoring Mithra, the angel of light, truth, and covenant, reflecting the high value placed on these principles in Persian society. It served as a time of thanksgiving for the harvest and the blessings of the agricultural cycle [initial query], while also focusing on strengthening social bonds and promoting harmony within the community. Marking the autumnal equinox, it also represented a time of balance and transition. The festival's emphasis on covenant and friendship suggests the importance of social cohesion and trust in ancient Persian society, possibly linked to the stability required for successful agricultural practices and overall community well-being.

Tirgan (تیرگان): Invoking the Rains

Tirgan was a rain festival celebrated in July, associated with Tishtrya, the Zoroastrian yazata of rain and the star Sirius. The festival also commemorated a legendary archery contest that determined the boundaries between Persia and Turan. The association of Tirgan with both a Zoroastrian deity and a mythological event highlights the integration of religious beliefs and national identity in ancient Persian festivals.

The rituals of Tirgan primarily involved water-related activities, such as splashing water on each other, symbolizing the hope for rain. Traditional archery was also practiced, reenacting the legendary contest. The water rituals directly reflect the festival's purpose of celebrating and invoking rain, demonstrating a clear connection between their religious practices and agricultural necessities.

The symbolic meanings of Tirgan included honoring Tishtrya and seeking blessings for sufficient rainfall for crops. It also served to remember and celebrate a significant event in Persian history and mythology. Furthermore, Tirgan reinforced the importance of water as a life-giving element, crucial for agriculture and survival. This festival underscores the vital significance of water in the often arid climate of Persia and how this necessity was woven into their religious and cultural observances.

Sadeh (سده): Mid-Winter's Light

Sadeh was a mid-winter festival, celebrated fifty days (and nights) before Nowruz. It was a festival of fire, symbolizing the defeat of darkness and cold, and welcoming the approaching spring. Legend attributes its origin to the discovery of fire. The timing of Sadeh, occurring fifty days before Nowruz, suggests a deliberate marking of the midpoint between the winter solstice and the spring equinox, indicating an awareness of the solar calendar.

The central ritual of Sadeh involved lighting large bonfires. Communities would gather to celebrate, often with music and dancing, fostering social unity. The communal nature of Sadeh, with its large bonfires and shared festivities, emphasizes the importance of community spirit in overcoming the challenges of winter and anticipating the arrival of spring.

The symbolism of Sadeh focused on the defeat of darkness and cold through the power of fire, a fundamental Zoroastrian symbol. It also served to welcome the coming of spring and the renewal of life, and to commemorate the discovery of fire, a pivotal event in human history and a revered element in Zoroastrianism. Sadeh's emphasis on fire as a symbol of victory over darkness aligns with the broader Zoroastrian theme of light triumphing over evil, specifically applied to the physical challenges of winter.

Sepandarmazgan (سپندارمذگان) or Esfandegan (اسفندگان): Honoring Love and Earth

Sepandarmazgan, also known as Esfandegan, was an ancient Persian festival dedicated to love and the earth. It honored Sepandarmaz (Spenta Armaiti), the Zoroastrian Amesha Spenta representing devotion, serenity, and the Earth. Traditionally celebrated on the fifth day of the month of Esfand (February/March), it is sometimes referred to as the Persian Valentine's Day. The dedication of a festival to both love and the Earth goddess highlights the ancient Persian reverence for the feminine principle and the life-giving power of the earth.

The primary tradition of Sepandarmazgan involved men giving gifts to women and honoring them, emphasizing the importance of women in society and the home. This custom suggests a recognition of women's vital role in the family and community, potentially linked to their contributions to agriculture and nurturing life.

The symbolism of Sepandarmazgan centered on honoring Sepandarmaz, representing devotion, serenity, and the Earth, reflecting the importance of these qualities. It also celebrated love and the strengthening of relationships, and acknowledged the sacredness of the Earth and its life-sustaining properties, crucial for agriculture. Sepandarmazgan provides a unique insight into the ancient Persian worldview, where love and the Earth were intertwined as fundamental and revered aspects of existence, possibly reflecting a deep ecological awareness.

Zoroastrian Seasonal Festivals (Gahanbars): A Cycle of Observances

The Zoroastrian calendar also included six seasonal festivals known as Gahanbars. These festivals marked distinct stages of creation and the agricultural cycle, providing a structured framework for connecting with the natural world and their faith.

Table 1: Zoroastrian Seasonal Festivals (Gahanbars)

| Festival Name | Approximate Timing | Significance | Connection to Agriculture/Creation |

| Maidyozarem | Mid-spring | Renewal of life, start of growing season | Beginning of agricultural activity, growth and fertility |

| Maidyoshahem | Mid-summer | Peak of growing season, beginning of harvest? | Maturation of crops, anticipation of harvest |

| Paitishahem | Autumnal Equinox | Bringing in the harvest, thanksgiving | End of harvest season, celebration of agricultural abundance |

| Ayathrem | Early Winter | Bringing home the herds | Importance of livestock, securing resources for winter |

| Maidyarem | Mid-winter | Rest and reflection during agricultural off-season? | Period of dormancy in nature, potential focus on community and spiritual renewal |

| Hamaspathmaidyem | End of Winter | Feast of All Souls, just before Nowruz | Honoring ancestors before the cycle of rebirth, preparation for the new agricultural year |

These Gahanbars demonstrate a systematic integration of religious observance with the practical realities of their agrarian lifestyle, with each festival aligning with key agricultural activities and seasonal changes.

Monthly Festivals (Name-Day Celebrations): Dedicated to the Divinities

A unique aspect of the Zoroastrian calendar was the concept of monthly festivals. Both the days and the months were named after divinities. When the name of a particular day coincided with the name of the month, it was considered a special festival day dedicated to that specific divinity. This structure permeated daily life with religious significance, constantly reminding people of the divine presence in the world around them.

Table 2: Zoroastrian Monthly Festivals (Name-Day Celebrations)

| Festival Name | Day & Month Name Coincidence | Dedicated Divinity | Associated Significance |

| Farvardinagan | Farvardin roj & mah | Fravashis (guardian spirits) | Honoring ancestral spirits and their protective role |

| Ardibeheshtgan | Ardibehesht roj & mah | Asha Vahishta (Best Righteousness, Fire) | Dedication to divine order and the sacred element of fire |

| Khordadgan | Khordad roj & mah | Haurvatat (Wholeness, Perfection, Water) | Celebration of perfection and the life-giving power of water |

| Tirgan | Tir roj & mah | Tishtrya (Rain and Sirius) | Honoring the yazata of rain and the star associated with it |

| Amardadgan | Amardad roj & mah | Ameretat (Immortality, Plants) | Celebration of immortality and the vital role of plants in sustaining life |

| Shahrivargan | Shahrivar roj & mah | Khshathra Vairya (Desirable Dominion, Metals & Sky) | Dedication to righteous dominion, the sky, and the strength associated with metals |

| Mihragan | Mihr roj & mah | Mithra (Friendship, Covenant, Light) | Honoring the angel of friendship, truth, and the divine light |

| Abanegan | Aban roj & mah | Anahita (Goddess of the Waters) | Dedication to the goddess of water and its purity |

| Azargan | Azar roj & mah | Atar (Fire) | Honoring the divine presence in fire |

| Deygan | Dae roj & mah | Ahura Mazda (Wise Lord) | Multiple dedications to the supreme creator |

| Bahmanjan | Bahman roj & mah | Vohu Manah (Good Purpose, Animals) | Dedication to good thought and the animal kingdom |

| Esfandegan | Spendarmad roj & mah | Sepandarmaz (Devotion, Earth) | Honoring devotion, serenity, and the sacred Earth |

This system of naming days and months after deities indicates a deep integration of religion into the fabric of timekeeping, where every day held a potential connection to the divine.

Enduring Legacy: Modern Observance of Ancient Traditions

Many of these ancient Persian occasions continue to be celebrated today, albeit with varying degrees of prevalence. Nowruz remains the most widely and vibrantly celebrated, not only in Iran but also among Persian-speaking communities across the globe. Many of its ancient rituals and traditions are still meticulously observed, and it has even gained international recognition from UNESCO and the United Nations. Yalda Night also continues to be a significant cultural celebration in Iran and other Persian-influenced regions, with families faithfully gathering to observe its traditional customs, and it too has been recognized by UNESCO. Chaharshanbe Suri, the fiery prelude to Nowruz, remains a popular tradition in Iran, although its observance may have seen some evolution over time. While perhaps less universally observed than Nowruz and Yalda, Mehregan still holds cultural significance for some Persian communities, often marked by gatherings and expressions of gratitude.

The observance of these ancient Persian occasions has inevitably evolved over time, influenced by factors such as the advent of Islam, modernization, and globalization. For instance, Nowruz has remarkably persisted as a key civil holiday even through periods of significant political and religious change. The continued vibrant celebration of Nowruz and Yalda, despite centuries of societal transformations, underscores the deep cultural resilience and enduring importance of these traditions in Persian identity. These festivals fulfill fundamental cultural and social needs, connecting people to their rich heritage and providing a sense of continuity across generations.

Conclusion: A Timeless Tapestry

The occasions of old Persia reveal a profound and intricate connection between the Zoroastrian faith and the cyclical rhythms of agriculture. These celebrations provided a framework for understanding the world, reinforcing religious beliefs through ritual and symbolism, and celebrating the essential bounty of nature. From the grand spring festival of Nowruz to the mid-winter vigil of Yalda, and the monthly dedications to various divinities, these traditions wove a rich tapestry that defined the cultural and spiritual life of ancient Persia. Their lasting cultural and historical importance is evident in the continued observance of many of these traditions in the modern era, serving as a testament to the enduring power of heritage and the deep-rooted values of faith, community, and the natural world.