In the milieu of 9th‑ and 10th‑century Greater Iran, a cultural flowering known as the Samanid Renaissance laid the groundwork for the classical Persian literary tradition. At its heart stood Abu Abd Allah Ja‘far ibn Muhammad Rudaki (c. 858–940 CE), a poet whose mastery of New Persian verse earned him the title “Father of Persian Poetry.” Through his elegant imagery, musical language, and versatility across poetic forms, Rudaki both exemplified and propelled the revival of Persian as a courtly and literary language.

1. The Samanid Court: A Cradle for Persian Culture

When the Samanid dynasty (819–999 CE) established its capital at Bukhara, it consciously promoted Persian language and culture after two centuries of Arabic political dominance. Under rulers like Ismail I and Nasr II, Persian became the language of administration, scholarship, and the arts:

-

Patronage of Poets and Scholars. The Samanids welcomed writers, theologians, and lexicographers—creating a vibrant courtly scene.

-

Standardization of New Persian. A standardized script (the Perso‑Arabic alphabet) and the infusion of Arabic religious and technical vocabulary enriched Persian’s expressiveness.

-

Cultural Synthesis. Pre‑Islamic Iranian motifs (royal glory, epic heroes) blended with Islamic ethics and cosmology, forming a unique Persian‑Islamic identity.

It was into this environment that Rudaki was born—likely in Ḥudāt, in modern Tajikistan—and brought to Bukhara as a child, where his prodigious talent quickly caught the eye of patrons.

2. Rudaki’s Life and Literary Beginnings

Details of Rudaki’s biography are sparse, but tradition preserves key moments:

-

Early Talent. By his teens, Rudaki was renowned for his melodic recitations and skill in composing on the spot—earning him a place in the court of Amir Nasr II.

-

Court Poet to Nasr II. From around 892 CE until his sudden fall from favor circa 931 CE, Rudaki presided over poetic gatherings, composed qasidas (odes), ghazals (lyric couplets), rubā‘īs (quatrains), and even the earliest known dastans (prose‑poetic narratives).

-

Blindness and Decline. In later life, Rudaki lost his sight—according to some accounts through royal envy—and died in obscurity. Legend holds he spent his final days begging, reciting his verses for alms.

Despite the tragic arc, Rudaki’s output—quoted by later anthologists like Dawlatshah and Jami—secured his place as a foundational figure.

3. Innovations in Form and Imagery

Rudaki’s genius lay in both formal mastery and creative freshness:

A. Versatility of Forms

-

Qasida: Rudaki perfected the courtly ode, balancing panegyric praise of the ruler with vivid descriptions of nature.

-

Ghazal: He helped elevate the lyric couplet into a vehicle for personal reflection and romantic expression.

-

Rubā‘ī: His quatrains display philosophical insight and linguistic precision.

-

Dastan (Prose‑Poetry): Early narratives like the lost Yārnāmah hint at Rudaki’s role in shaping Persian storytelling.

B. Nature and Emotion

Rudaki’s verses often draw on pastoral motifs—gardens, birds, running water—to mirror human states of joy, longing, and sorrow:

“When the nightingale sings in the rose’s shade,

Each leaf of the garden whispers your name.”

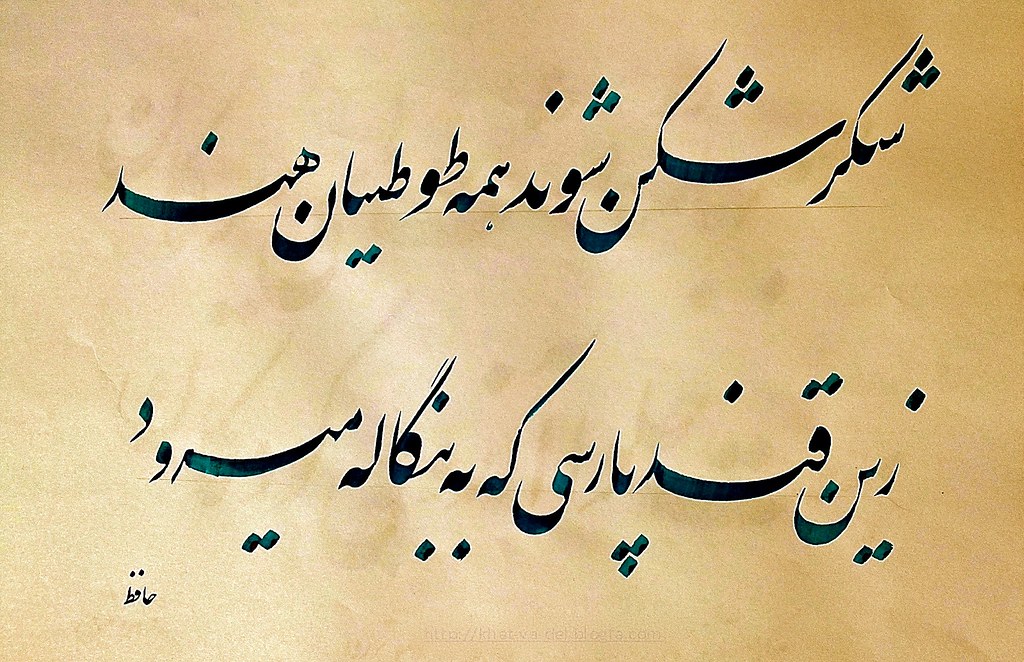

Such lines set a precedent for later poets like Hafez and Saadi, who expanded on nature’s symbolic resonance.

C. Linguistic Clarity

While later classical Persian poetry became increasingly ornate, Rudaki’s language remained remarkably transparent—each word chosen for its sound and sense, ensuring that his poetry was as accessible to common listeners as to court elites.

4. Legacy and Influence

Though only fragments of Rudaki’s estimated tens of thousands of verses survive, his impact radiates through Persian literature:

-

Model for Successors. Every major poet—Ferdowsi, Daqiqi, Attar, Rumi—drew upon Rudaki’s formal innovations and thematic palette.

-

Standardization of Persian Poetics. Rudaki helped codify meters and rhyme schemes that became the backbone of the classical tradition.

-

Cultural Memory. His reputation endured in biographies and anthologies; in modern Iran and Tajikistan, Rudaki’s name graces streets, institutions, and even a national prize for literature.

In reviving Persian as a literary medium, Rudaki did more than compose beautiful verses—he reclaimed a cultural heritage and set the stage for centuries of poetic brilliance.

5. Conclusion: A Voice Across the Ages

Rudaki’s life and work capture the spirit of the Samanid Renaissance: a time when Persian language and identity were reborn, and poetry became both courtly craft and collective soul‑music. Though age and tragedy dimmed the light of his verses, his influence remains a guiding beacon. As modern readers, we glimpse in Rudaki’s surviving lines the first notes of a long poetic symphony—one that continues to resonate in every garden of Persian verse.