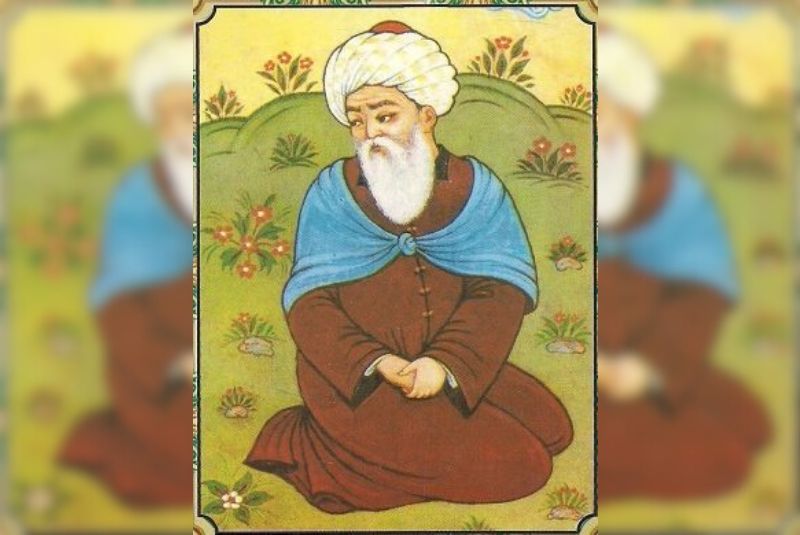

Long before Rumi’s soaring verses filled the courts and khanqahs of medieval Persia, another poet quietly forged the language of Sufi mysticism into lyrical form. Abū al-Majd Majdūd ibn Ādam Sanāʾī Ghaznawī (c. 1080–1131 CE)—known simply as Sanai—laid the groundwork for the great spiritual epics that followed, weaving philosophy, ethics, and divine longing into the first truly “Sufi” Persian masnavi.

1. A Poet of Two Worlds: Court and Cloister

-

From Ghazni’s Palaces… Sanai served at the glittering Ghaznavid court of Sultan Masʿūd III, mastering the classical forms of panegyric (qasida) and lyrical quatrain (rubā‘ī). He was equally at ease praising royal patronage and extolling the virtues of justice and generosity.

-

…To the Path of the Heart. A profound spiritual turning point—some say a vision of the Prophet Muḥammad—propelled Sanai from courtly poet to mystic teacher. He retreated from politics to pursue and share inner wisdom.

This duality—courtier and wandering dervish—infuses his work with both rhetorical polish and heartfelt urgency.

2. Hadiqat al‑Haqqīqa (“The Walled Garden of Truth”)

Sanai’s masterpiece, completed around 1121 CE, stands as the first major Persian masnavi dedicated entirely to Sufi doctrine.

-

Structure: Over 10,000 couplets in rhyming masnavi form, divided into thematic chapters on tawḥīd (unity of God), love, morality, repentance, and the stages of the spiritual path.

-

Blend of Genres: Fables, anecdotes, direct address, and Qur’anic citations mingle freely—each story functioning as both narrative delight and moral mirror.

-

Key Anecdote: The tale of the moth who sacrifices itself in the flame becomes a powerful emblem of fanāʾ (annihilation of the ego) and baqāʾ (subsistence in God).

“O you whose heart is veiled by dust of self—

Dare to leap into the fire of Love itself.”

Sanai’s voice here is intimate yet universal, addressing both novice seeker and seasoned dervish.

3. Themes That Shaped Persian Mystical Verse

-

Unity of Being (Wahdat al‑Wujūd): Sanai’s poetry emphasizes that all existence flows from a single divine source—an idea later magnified by Ibn ʿArabī and Rumi.

-

Ethics as Foundation: Moral conduct—justice, generosity, humility—is not an optional accessory but the very soil in which mystical insight grows.

-

Love as Cosmic Power: Divine Love is more than emotion; it is the force that births and sustains the universe, drawing all beings back to their origin.

-

The Role of the Master: Sanai underscores the necessity of a spiritual guide to navigate the perils of ego‑bound seeking—a motif central to later Sufi literature.

4. A Legacy Carried Forward

Sanai’s influence rippled outward in two waves:

-

Attar of Nishapur (d. c. 1221): Drew heavily on Sanai’s his garden‑of‑truth motif and his allegorical style in Conference of the Birds.

-

Jalāl al‑Dīn Rūmī (1207–1273): Aware of Sanai’s teachings, Rumi expanded them into the vast ocean of his Masnavi-ye Ma‘navi, echoing Sanai’s couplets and moral urgency.

Even in later periods, poets like Jami and Saadi paid homage to Sanai’s pioneering blend of didactic prose and ecstatic verse.

5. Reading Sanai Today

-

Dip Into the Garden: Start with a single chapter of Hadiqat al-Haqqiqa. Notice how each anecdote segues into a quatrain that crystallizes its lesson.

-

Look for the Master’s Hand: Observe how Sanai balances narrative drama with direct addresses—“O soul,” “O seeker,” “O king”—inviting you into dialogue.

-

Trace the Echoes: As you read Rumi or Attar, watch for familiar images—the moth, the candle, the mirror—that originated in Sanai’s fertile imagination.

Conclusion

Sanai stands at the threshold of classical Persian mystic poetry: the first to plant the seed, the gardener who tended it with both exquisite form and fiery devotion. Without his “Walled Garden of Truth,” the lush forests of Rumi’s epic, Attar’s allegory, and Saadi’s moral vision might never have grown. Today, reading Sanai is like returning to the wellspring—drinking of waters both ancient and eternally fresh.