Persian literature, renowned for its lyricism, mysticism, and philosophical depth, also boasts a long and rich tradition of satire—a genre used not only to entertain but to challenge hypocrisy, criticize injustice, and provoke thought. From the biting wit of Obayd Zakani in the 14th century to the works of modern Iranian authors, satire has served as a mirror held up to society, reflecting its absurdities, contradictions, and corruptions with both laughter and rage.

Obayd Zakani: The Master of Persian Satire

One cannot speak of Persian satire without beginning with Obayd Zakani (d. c. 1370), a sharp-tongued poet whose pen spared no one—from corrupt clerics to pompous kings.

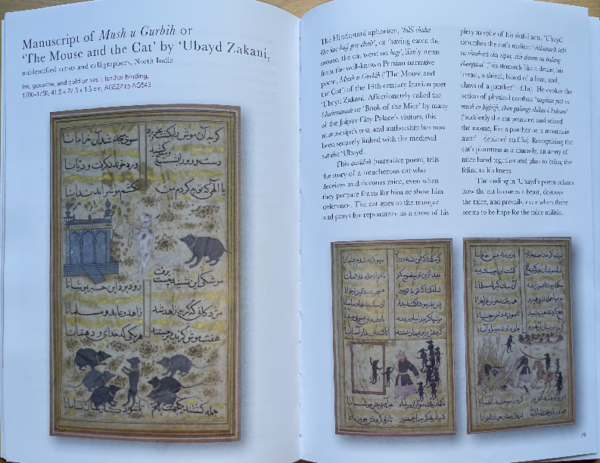

Living during a time of political upheaval and social decay, Zakani used humor, irony, and grotesque imagery to critique the moral pretensions of his time. His most infamous work, "The Mouse and the Cat" (Mush-o Gorbeh), is a fable cloaked in playful rhyme, yet seething with political and religious satire.

“The mullah preaches piety by day,

And drinks and sins when out of the way.”

Zakani’s poetry ridiculed the gap between public virtue and private vice, exposing how power often hid behind a veil of sanctity. His boldness remains striking even today—he dared to say what others feared to think.

The Satirical Tradition Lives On

While Obayd Zakani laid the foundation, satire in Persian literature didn’t end with him. Across centuries, writers have used humor as a subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) means to critique their world.

Saadi, for instance, though known for his wisdom and elegance, sprinkled Golestan and Bustan with ironic tales and humorous anecdotes that challenged superficial piety and empty power.

Hafez too—while not strictly a satirist—used clever double meanings (iham) to mock religious hypocrisy and corrupt leaders under the guise of romantic or mystical verse:

“They preach abstinence, but sip wine in secret.

Do not be fooled by the sermon—they know the tavern well.”

Modern Voices: New Masks, Old Questions

In modern Iran, satire has taken on new forms—from poetry and prose to film, comics, and online media. The tradition continues, often under pressure from censorship, but never silenced.

Writers like Iraj Pezeshkzad, author of My Uncle Napoleon, used comedic storytelling to comment on family dynamics, paranoia, and the absurdities of power. Published in the 1970s, the novel became an iconic series and remains a cultural reference point, thanks to its brilliant blend of humor and critique.

More recently, internet satire and cartoons have flourished as powerful forms of dissent. Social media has become the new tavern—where wit and courage mix, and truth is spoken with a wink.

Why Satire Matters

Satire matters because it cuts through pretense. It disarms by making us laugh, but leaves us thinking long after the joke. In societies where direct criticism may be dangerous or taboo, satire offers a vital outlet—a way to question the unquestionable.

In Persian literature, satire is not merely mockery; it is moral. It is the voice of conscience dressed in humor. Whether penned by Obayd Zakani centuries ago or posted by a modern cartoonist online, the satirical voice speaks for the people, challenges the powerful, and reminds us that truth often hides in jest.

Final Thoughts

From the poetic subversion of Zakani to the sharp wit of modern satirists, satire in Persian literature is more than comic relief—it's a literary tradition rooted in courage, intellect, and love for truth. As long as there is injustice to expose and hypocrisy to unveil, satire will thrive, laughing at the powerful and standing with the people.

In laughter, there is liberation. And in satire, a blade disguised as a smile.