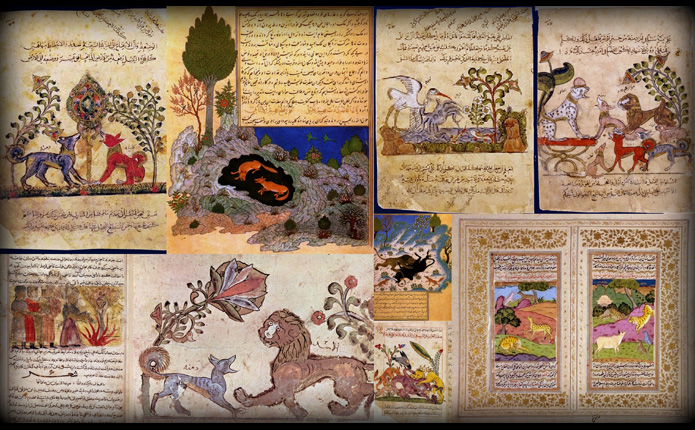

In the vast literary landscape of Persian culture, one fascinating genre serves as both a mirror of the literary tradition and a window into the lives of its creators: the Tazkireh (also spelled Tadhkira or Tazkirah). These biographical anthologies—part biography, part literary criticism, part anthology—form an essential part of Persian literary history. They don’t just list names and dates; they capture the spirit of the literary world, offering glimpses into poetic circles, patronage systems, social values, and aesthetic ideals across centuries.

What Is a Tazkireh?

A Tazkireh is a literary-biographical compilation, usually written in prose, that records the lives and selected works of poets and writers. These collections often include:

-

Brief biographies (with anecdotes, lineages, or personal traits),

-

Sample verses (usually the author’s favorites or those most admired at the time),

-

Critical remarks (praise, comparison, or commentary on style or originality),

-

Social or historical context (like court affiliations, rivalries, or political events).

Think of a Tazkireh as a blend of a literary journal, a who's-who directory, and a cultural memoir.

The Roots and Rise of the Genre

While earlier Persian texts occasionally included biographical sketches (especially in court histories or Sufi hagiographies), the Tazkireh as an independent literary form began to flourish from the 13th century onward, drawing inspiration from Islamic traditions of Hadith transmission and Sufi genealogies. It reached its peak between the 16th and 19th centuries, especially in Persianate courts across Iran, Central Asia, India, and the Ottoman Empire.

Famous Tazkirehs in Persian Literature

-

Tazkirat al-Awliya’ by Attar of Nishapur (12th century)

– While more focused on saints and mystics than poets, this early example shaped the spiritual tone of later biographies. -

Lubab al-Albab by Awfi (13th century)

– One of the earliest Persian literary tazkirehs, it includes poets from early Islamic centuries to the author's time, along with engaging anecdotes. -

Majmaʿ al-Fusaha by Reza Qoli Khan Hedayat (19th century)

– A key Qajar-era tazkireh with detailed biographies and poetic samples, serving as a bridge to modern literary criticism. -

Tazkireh-i-Nasrabadī by Nasrabadī (17th century)

– Known for its elegance and wit, offering insight into Safavid poetic taste and court culture. -

Tazkireh-i-Hindī and Dakhani anthologies

– Reflect the vibrant Indo-Persian literary scene, especially during the Mughal period, including Urdu and Persian poets.

More Than Biography: Cultural and Aesthetic Insights

What makes tazkirehs truly valuable is their literary perspective. They are not neutral accounts; they’re full of preferences, biases, poetic tastes, and ideological leanings. Through these texts, we can:

-

Trace literary trends: Which poetic forms were in vogue? Whose metaphors were admired? Who broke tradition?

-

See networks of influence: Who studied with whom? Which patrons supported the arts? What schools of poetry emerged?

-

Catch glimpses of daily life: Through anecdotes—both reverent and humorous—we learn about love, loss, rivalry, exile, and devotion.

Some entries read like fan tributes, others like critiques, and some offer surprisingly candid insights into the struggles of a poet’s life.

The Tazkireh in the Modern Era

In modern literary scholarship, tazkirehs are essential primary sources. They help reconstruct literary history, offering:

-

Linguistic evolution (changes in vocabulary, form, and metrics),

-

Sociopolitical history (especially regarding patronage, censorship, and diaspora),

-

Gendered perspectives (though rare, some tazkirehs mention women poets, especially in Indian and Ottoman contexts).

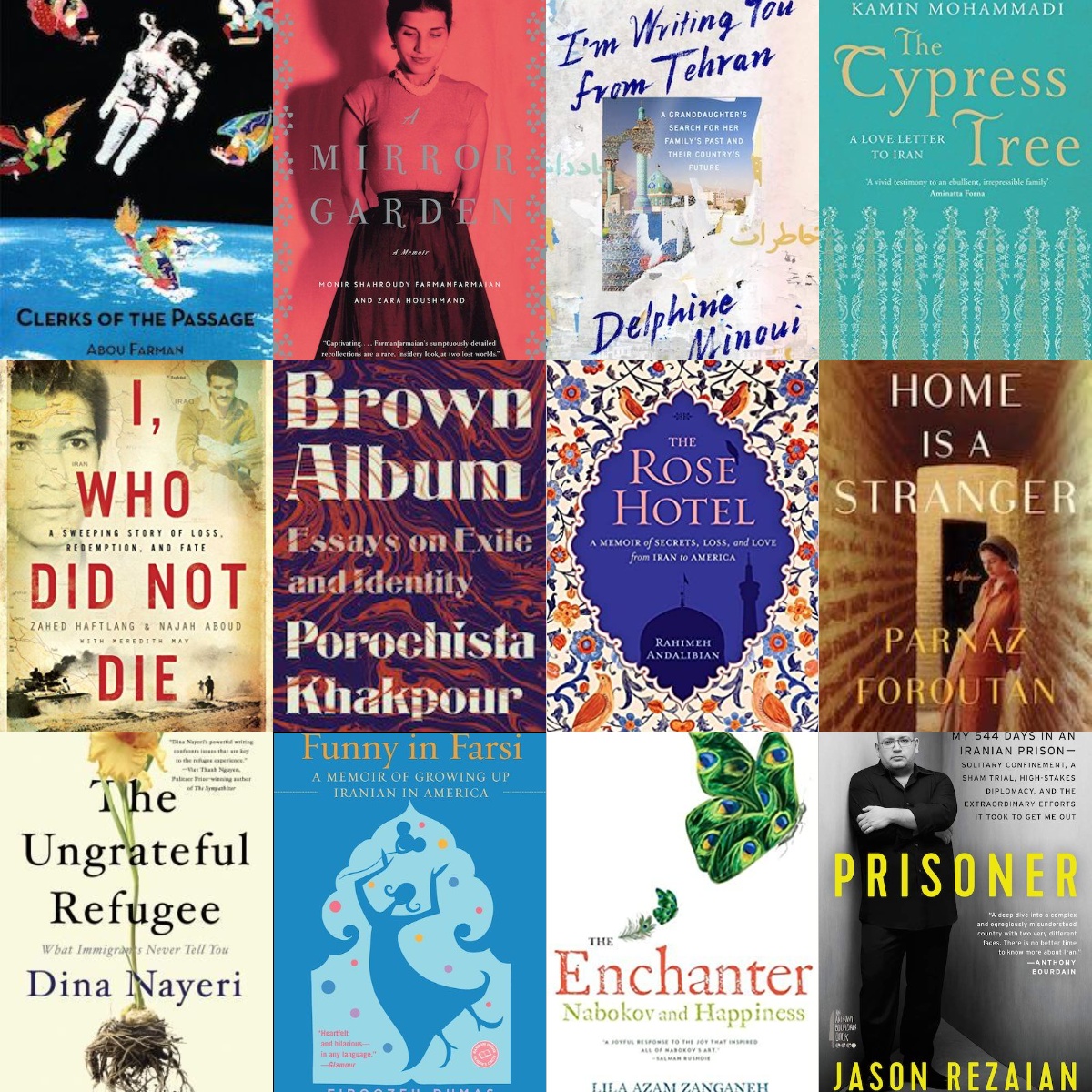

Moreover, the genre has inspired modern equivalents—literary magazines, critical anthologies, and even Wikipedia-style repositories—all echoing the spirit of the original tazkirehs.

Writing a Tazkireh Today

Modern scholars, poets, and enthusiasts can draw inspiration from this genre by:

-

Creating curated anthologies of contemporary Persian or Persian-inspired poets,

-

Reviving tazkireh-style biography with a modern lens (e.g., incorporating digital media),

-

Exploring forgotten poets from older tazkirehs and bringing them to light.

Conclusion

The Tazkireh is not merely a list of poets—it is a portrait of a literary world, drawn with affection, critique, humor, and reverence. It invites us into the salons, courts, and Sufi lodges of the past, where verses were debated, hearts broken, and reputations forged through words. In an age of data and digital profiles, revisiting the tazkireh reminds us that literature is not just made of texts—it is made of lives.

So, the next time you read a Persian poem, remember: behind every verse may lie a tale worthy of a tazkireh.