Long before the grandeur of the Safavids or the mystic outpourings of Rūmī, a small Iranian dynasty in the heart of Central Asia ignited a brilliant literary flame. The Samanid era (819–999 CE) laid the cultural and linguistic foundations for what we now know as classical Persian poetry. Here’s how this dynamic dynasty transformed Persian from a spoken vernacular into a storied literary language that would echo across centuries.

1. Historical Background: A Persian Resurgence

After the Arab conquests of the 7th century, Arabic became the language of administration, law, and high culture across much of the Islamic world. Local Iranian dynasties often adopted Arabic for official business, while regional tongues survived in oral use.

Enter the Samanids, a family of Iranian governors based in Bukhara and Samarkand who, by the early 10th century, had asserted practical independence from the Abbasid Caliphate. Proud of their Persian heritage and eager to strengthen internal cohesion, the Samanid rulers made a bold cultural choice: to revive New Persian as both an administrative and literary language.

2. Establishing New Persian on the Page

-

Adopting the Arabic Script

To give Persian a permanent written form, the Samanids adopted the Arabic alphabet—adding a handful of characters to represent Persian sounds. This innovation made texts easier to copy on the same paper and in the same workshops that produced Qur’an manuscripts. -

Court Decrees and Poetry Side by Side

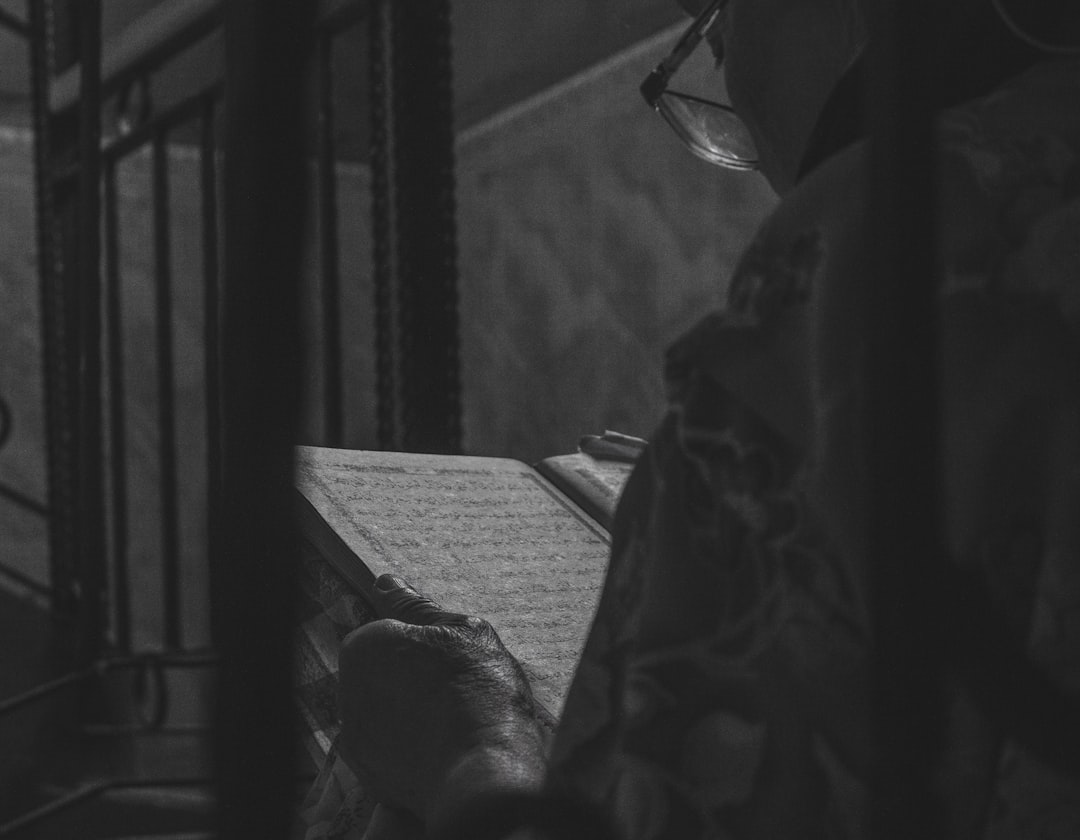

Persian began appearing in official decrees, coinage, and correspondence alongside or even in place of Arabic. At the same time, court secretaries experimented with rendering oral poetry in this newly standardized script, setting the stage for a flourishing of written verse.

3. Rudaki and the Dawn of a Literary Tradition

Often hailed as “the father of Persian poetry,” Abū ʾAbd Allāh Jaʿfar Rudakī (d. ca. 955 CE) was the Samanid court poet at Bukhara. Under the patronage of Nūḥ ibn Asad and later Amīr Abd al-Malik, Rudakī:

-

Composed Panegyrics (qasīdas) celebrating royal virtues, military victories, and the bounty of the land.

-

Codified Courtly Conventions, including the nasīb (love-infused opening), journey-scene, and final prayer—patterns that would define Persian qasīda for centuries.

-

Mentored a Generation of secretaries and poets, transmitting both meter (borrowed from Arabic ʿarūḍ) and local imagery—vineyards, falcons, mountain springs—that grounded his work in Iranian soil.

Though much of his divan survives only in excerpts, Rudakī’s impact was profound: he proved that Persian could match Arabic for elegance, nuance, and emotional depth.

4. Patronage and the Rise of Literary Circles

-

Royal Workshops

Samanid courts cultivated their own ateliers, where poets, calligraphers, and scholars gathered. These salons—linked to madrasas and libraries—became hubs of intellectual energy, much like the later Timurid madrasas of Herat. -

Visions of a Persianate Realm

Sponsors such as Amīr ʿAbd al-Malik and his successor Amīr Abd al-Manṣūr recognized that a standardized Persian literary culture could bind diverse peoples—from Tajiks to Sogdians—into a shared identity. Their endowments to schools and libraries ensured that poetry circulated far beyond Bukhara’s city walls.

5. Administrative Uses: Poetry Meets Statecraft

The Samanid embrace of Persian had practical benefits:

-

Accessible Governance: Local officials and merchants found it easier to read orders and tax registers in their mother tongue.

-

Legal and Scientific Texts: While Arabic remained the language of theology and philosophy, Persian quickly became the medium for medical manuals, historical chronicles, and treatises on astronomy—making knowledge more widely available.

This dual-track approach—Arabic for the sacred, Persian for the everyday—set a template for later Islamic polities from the Ghaznavids to the Mughals.

6. Long-Term Legacy: A Language Takes Flight

By the late 10th century, New Persian had achieved literary maturity under Samanid auspices. Within a few generations:

-

Epic Poets like Ferdowsī could confidently compose 50,000-line masterpieces in Persian.

-

Sufi Mystics such as Balʿamī and later Rūmī found in Persian a supple vehicle for mystical allegory.

-

Courtly Lyricists from Saʿdī to Ḥāfiẓ spun ghazals that remain world-famous to this day.

Today’s readers—whether in Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, or diaspora communities—still turn to those classical works, many of which trace their origins back to that crucial Samanid moment when Persian first claimed its place on the page.

7. Conclusion: The Samanid Gift

The Samanids did more than collect taxes or wage wars; they nurtured a language into full bloom. By empowering poets like Rudakī, standardizing script, and blending oral tradition with written culture, they laid the cornerstone of the Persian literary edifice.

“From Bukhara’s minarets to distant lands,

Persian verse took wing—on Samanid wings it flew.”

When we read a couplet of Hafez or lose ourselves in Ferdowsī’s epic saga, we participate in that same cultural revival—a testament to the enduring power of patronage, vision, and the written word.